Traditional Russian Village Structure

Updated 13 May 2005

Russian villages consisted of wooden houses, the church, the bathhouse, windmills, storage sheds and other outbuildings spaced to prevent the spread of fire.

The pogost village was originally a country church with its related structures.

The svoboda or sloboda village was exempted from the work obligation to the state.

The selo was a market town or large village.

The derevnia was a small hamlet, usually without church, supply store, etc.

Hills, woodlands, rivers, sun and prevailing winds affected village layouts. The linear arrangement is the most ancient type with the buildings set in lines along the bank of a lake or river, or along side a road.

Bathhouses might be built in a cluster near the local body of water. Storage sheds and crafts workshops were often grouped at the edge of the village. Crafts were often done communally.

The farmland was divided into narrow strips with each household assigned several strips spread among the village's land holdings. These lots were rotated among the households, usually based on the number of taxable people in each family. This made equitable distribution of the arable land, but made farming less efficient. This distribution of farmland is essentially identical to the method used in medieval England.

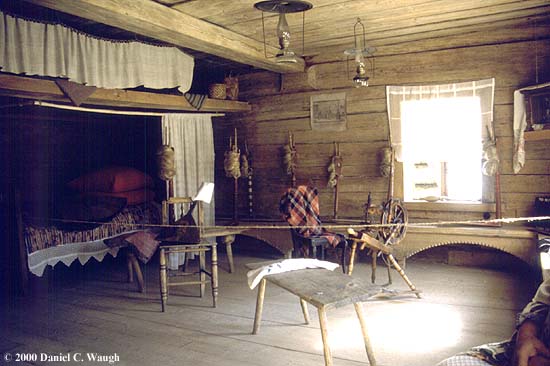

The typical farmstead was the house, izba, set close to the street, a barn, a hayshed, and the kitchen garden. The outbuildings were arranged to form a yard, dvor, enclosed by a low fence of sticks or woven twigs. In the northern parts of Russia, the outbuildings were connected to the main structures, while in the south they were spaced apart.

The houses were constructed of logs and were not very variable in layout, but they did have special architectural features that could be embellished. These included the ridgepole of the roof (okhlupen'), the gable ends (or pediments), the horizontal board that separated the triangular pediment from the square base of the house, the vertical boards at each corner ("towels"), and the frames of windows and doors (svetelochnii nalichnik). Decorative plant and animal forms, mythic and magical creatures, or initials and dates were among the personalizing motifs.

Wood was the most common building material. Metal was valuable and seldom used in nails for buildings. All parts of the building were cut and joined using a handaxe. Saws were rarely used. Archaeological excavations of Novgorod show how wood was used to pave streets, and make drains and gutters.

The classic peasant house is known as an izba. The word "izba" seems to be derived from istopka, bathhouse. Istopsa and istba came to refer to a house with a reception area, or to a building in general. The term klet' at first just meant a building with four walls, then designated the very simplest wood structures, while an izba was a house heated with a clay or tile oven.

Variations of the izba altered the size and number of walls. A piatstenok, literally five-walled, had an "extra wall" dividing living space from storage space.

The main room of the izba was defined by the large stove which made it the only heated room in the structure. It could accommodate ten to twenty people.

A separate storeroom, sometimes called a klet', might be below or to the side of the main room. And other structures might also be attached to the main building, especially in northern Russia.

Izbas came in three regional types.

Northern izbas, in the heavily forested areas of Arkhangel'sk, Olonets, Vologda, and Novgorod, had living areas raised off the ground over a cellar, called a podklet', or over stables (to take advantage of the animals' warmth). The structures tended to be arranged in an L or U shape around a courtyard, to hold extended family, livestock, storage for hay and grain, a bath house and a well.

Central Russian izbas, between the Volga and Smolensk, were smaller, with attached or separate sheds for storage and livestock arranged a variety of ways.

Southern izbas, around Kaluga, Orel, Kursk, Voronezh, and Tambov, usually lacked basements and had adjacent sheds and enclosed yards for livestock.

In the north and in the Volga area, the arrangement of the outbuildings provide many areas for decoration, such as the covered stairs and passages between buildings. Carving, in the form of openwork tracery, embellished the eaves, the window frames and the balcony. Painting was sometimes added under wide eaves and balconies where it would be protected from the weather. Another important architectural element in the north was the okhlupen', or konek, a large figure carved from the root end of the larch tree and used as the house's ridgepole. They took the form of a horse, duck, chicken or deer, and probably represented an ancient Slavic or Scandinavian form, perhaps once representing a nature deity or protective spirit.

Along the Volga, houses were simpler and the facade facing the street was broader with the entrance at the front rather than the side (?). They were built of two-foot-thick pine logs and so the design of a simple izba was dominated by strong horizontals and the notched corners. Around Gorodets and Nizhnii Novgorod, elaborate carving set off the architectural elements. (The development of architectural carving in this region may be connected with Peter the Great's expansion of boatbuilding here. The Hilton book goes into more detail, but since that is definitely OOP, I won't go into it here.)

The Ukrainian peasant house, khata, was built of wood, stone or clay, usually covered with plaster and whitewash, with an earthen floor and thatched roof. Walls inside and out were often painted with bright designs.

The dominant feature of any izba was the large clay oven or pech' that occupied a corner to the left or right of the main door. The adjacent area, the chulan, was the women's side of the house and contained the water barrel, table for food preparation, and storage cupboards for dishes and cooking supplies. Raised sleeping platforms, polaty, fit next to the oven, sometimes extending over the entrance area to the opposite wall. Low benches, lavki, were built along the other walls and used for seating, sleeping, or sometimes to support freestanding cupboards. The large decorated loom usually stood in the center of the room. Wrought-iron lighting fixtures held wooden splints to provide light for evening and winter tasks. The spiritual focus of the home was the icon corner, located diagonally across from the oven. It was called the krasnyi ugol (beautiful corner) and had at least one icon, sometimes an icon case (bozhnitsa or kiot), embroidered linens and usually a small table with candles and family mementos. Anyone entering the izba would bow to the icons before greeting the hosts or speaking. Guests of honor were seated in the icon corner, and matchmaking rituals and parts of the marriage rites took place there. When a family member died, the body was laid out so the head lay toward the icon corner and the feet lay toward the door.

Generally, the interior walls were partly finished, planed and smoothed to a height of about 6 feet. In prosperous houses, important features were enhanced by carving or painting. The carving was not as elaborate as on the exterior, but the painting, protected from the weather, could be more lavish. Carved panels around the oven, pripechnye doski, painted to stand out from the whitewashed clay surfaces, were found in houses on the Volga. In Karelia, Archangel'sk and Vologda and east to the Urals, the tradition of painting interiors of churches in the 12th century and boyar houses in the 16th century, may have influenced the decoration of 19th century peasant homes.

Decorative painting included geometrical accents of structural features, freehand plants, animals and genre scenes, and trompe l'oeil wood and marble. Oil-based paint with ochre or red tones was preferred for contrast.

The combined effect of the bright-painted wood, carved utensils, textiles and candle-lit icons could be strikingly beautiful.

References:

Return to Russian Materials

Return to homepage