Men's Hair and Accessories in Early Rus

Updated on 15 July 2008

Hair:

- Hair was cut in a semi-circle (v skobky or v krushok). (Kireyeva)

Hair was worn “semi-long” in the back. It was trimmed evenly in a semi-circle in the back and then either combed outwards from the crown, occasionally with bangs covering the brow; or was combed back. Short hair was a sign of servitude. Other hairstyles are known, but they were atypical. (Stamerov)

Men always wore a beard with side burns and a moustache. (Kireyeva)

Beards and moustaches were worn as a sign of adulthood. Married men in particular

would grow a beard starting from the cheeks. This could be left broad and full, or

trimmed. Shapes included spade, double, blade-like, etc. The moustache was always

full and hung to or below the beard. Some earlier Rus princes wore only a long drooping

moustache, but after the time of Prince Vladimir Svyatoslavovich (early 1000s), the

beard was firmly established. (Stamerov)

Hairstyles underwent significant changes in the 13-17th cent. In the 13th cent. loose hair cut a little above the shoulder was in style. In the 14-15th cent. in northern Rus, or at least in Novgorod lands, men wore their hair long and braided it in a braid. (Rabinovich, 13-17)

For men were various styles – both for time and for territory. We already said that in the 15th cent. in Novgorod the Great and Pskov (possibly, in all the Novgorod land) men also braided hair in one braid. The wear of beards, evidently, was accepted for mature people. People younger might or might not wear a beard. We note that in the Novgorod initials part are depicted beardless people, at that the beard was not worn not only by the fishermen, but also the town crier – an official figure. Interestingly a description of marked simultaneously 26 robbers (city Shuya, year 1641). More than 2/3 of them (18 people) wore a beard (indication of color – for example “chermna ikrasna”, in other words, as would say now, red-haired; “pale” – and size – “great”, “small”). About 2 was said, that “they shaved”, about one – “sechet” [slashed? torn? whipped?], about 4: “youths, beards none, still not shaving”, finally about one simply – “beard none”. Until 15-16th cent. the beard and long hair and dark color of clothing was not required even for clergy. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

I have noticed a fairly wide variety of hairstyles in period art.

- Hats were an obligatory part of the costume of Rus. They came in a large

variety made of thick felt or broadcloth. They could be tall or short, and with or

without cap bands. (Kireyeva)

In studying headdress of the 9th-13th cent., it is necessary to consider that ancient depictions cannot give exhaustive information, in that the hierarchical presentations of that time compelled artists to depict men for the most part without headdress, in particular if in the drawing was a prince, which necessarily was drawn in a hat [In the presence of the prince, everyone else had to take their hats off.] Exceptions were made for a few church hierarchs, who are depicted in klobuki [ecclesiastical headdress]. Important depictions of skomorokhi [bards] are on the frescoes of the stairs of St. Sofia cathedral in Kiev. On their heads, two musicians have pointed hats [kolpak, колпак], with ends hanging a bit in back. A similar kolpak is on the head of the gusli player depicted on one of the Rusalka bracelets of the 12th century. Among archaeological finds is a dark-gray felt hat from the city of Oreshka and a round summer hat plaited from pine roots with a flat crown and rather large brim from Novgorod, reminiscent of the later Ukrainian bril’ [бриль], or stylish at the beginning of our century, kanot’e [канотье]. But this find is connected to a later period, the 14th to 15th centuries (Artsikhovskij, b.g., p. 286). One can only propose that peasants and ordinary city dwellers wore hats of fur, felt, and wicker, and that the fashion in headdress was diverse. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Conical caps with pointed tops made of felt or cloth were favored by commoners. Boyars tended to wear more rounded tall hats, or low semi-circular hats of expensive patterned fabrics. The hats could be lined with fur or also fabric, and constructed to make a roll or cuff, sometimes including earflaps. (Stamerov)

Besides entire robes, in the archaelogical monuments are known diverse parts of clothing, which were preserved almost completely. Thus, in the 13th century layers of Novgorod is found a man’s felt cap [shapka] in the form of a kolpak with a height of 20.5 cm. (Kolchin)Men's headdress underwent significant changes in the 13-17th cent. (One of these is the use of the skull cap, tafya or skufya. Starting in the 15th century?) (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Just as with the other garments worn in layers, for ceremonial excursions, one might wear several hats: a tafya (after the 15th cent), under a kolpak, under the gorlat hat! (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Kolpak/kalpak/klobuk:

-

In studying headdress of the 9th-13th cent., important depictions of skomorokhi [bards] are on the frescoes of the stairs of St. Sofia cathedral in Kiev. On their heads, two musicians have pointed hats [kolpak, колпак], with ends hanging a bit in back. A similar kolpak is on the head of the gusli player depicted on one of the Rusalka bracelets of the 12th century. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In the period of the 13-17th cent. the more widespread form of hat was probably the kolpak or kalpak. It was a tall, upward narrowing (sometimes such htat the top drooped over and hung down). Below, the kolpak had a narrow cuff with one or two breaks to wich were fastened decorations - buttons, zapony (cuffs?), and fur edging. The kolpak was distriubed extremely widely. They were "knitted" (the term includes naalbinding, crochet, etc.) and sewn from various materials, from simple linen and cotton to expensive wool. And they had various functions - sleeping, indoor, outdoor and ceremonial. A certain 16th cent. prince appropriated family valuables from his mother, including jeweled earrings for his sister's dowry that he used to decorate his kolpak, and never returned. Such a hat must have been quite elegant. The kolpak, or klobuk as it was then known, was widespread even in antiquity. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Shlyapa:

-

The men's shlyapy had round flaps, polki, and were sometimes made of felt, like the later peasant shlyapi. Such a shlyapa with a rounded crown and small, turned-up flap - evidently belonging to an ordinary citizen - was found in the city of Orezhka in a 14th century layer. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Fur shapkas - treukh, malakhaj, gorlatnaya shapka, cherev'i:

-

The warm men's headdress was the fur shapka. Sources call it treukh or malakhaj - shapka-ushanka, just as for women. The most formal was the gorlatnaya shapka which was made of the throat (gorlat) fur of rare animals. It was tall, widening upward, with a flat crown. Along with the gorlat hat is recorded also the cherev'i, made from fur taken from the belly of the animal. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Sun hats:

-

Among archaeological finds is a round summer hat plaited from pine roots with a flat crown and rather large brim from Novgorod, reminiscent of the later Ukrainian bril’ [бриль], or stylish at the beginning of our century, kanot’e [канотье]. This find is connected to the 14th to 15th centuries. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Royalty:

-

For the 9th-13th cent., well known by numerous depictions is the ancient Russian princely hat, this most important symbol of noble rule. The form of it is a half-spherical crown of bright material with fur (in all likelihood, sable) trim, and turns out to be extremely long lasting. The first depiction of a Russian prince in such a hat is connected to the 11th century. In the 14th century, a gold 8-wedge skullcap of Bukharskij work was received as a gift, and the Moscow prince ordered to attach to it a sable edging to increase its resemblence to the traditional princely hat, and only then did it become the great princely, and later also tsarist, crown - the "gold shapka" in the 14th century. This became the famous “Cap of Monomakh” in the beginning of the 16th cent. Above was placed a cross, however, in antiquity, the princely shapka was not crown with a cross. The tsar was crowned with it until the end of the 17th century. (Rabinovich, 9-13th c. and 13-17th c.)

Jewelry:

From the 10th through the 13th centuries, various items of jewelry were favored by men.

They included grivni, earrings, small crucifixes on chains or cords. Most jewelry was

made of metal. Nobles used mostly silver, but some gold. Poorer Rus had copper, bronze

or low-grade silver. (Stamerov)

From the 10th through the 13th centuries, various items of jewelry were favored by men.

They included grivni, earrings, small crucifixes on chains or cords. Most jewelry was

made of metal. Nobles used mostly silver, but some gold. Poorer Rus had copper, bronze

or low-grade silver. (Stamerov)

Jewelry was finely made. Pearlwork, silverwork, filigree and enameling are particularly prominent. (Kireyeva)

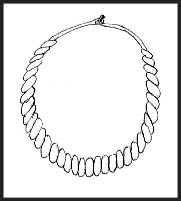

Grivni – an ancient form of necklace in the form of a heavy hoop of jute or braided wire, worn mostly by men. (Stamerov)

Earrings – earrings were worn by men, but only in one ear. The noble’s “three-bead” style was particularly popular. (Stamerov)

Rings - Among women's ornaments especially widespread in 10-15th cent were perstni (rings set with stones), although they were worn also by men. Perstni are one of the most numerous archeological finds among ornaments. They frequently repeated the forms of bracelets (twisted, woven, plastinchatye, etc.). The seal/signet persten had an individual form, as also Novgorodian perstni with settings - green, blue, light blue, black, transparent glass. Seal/signet perstni and Novgorodian with settings received dissemination not earlier than 13th cent. and existed right up until 15th cent. and even later. Representations on the signet/seal perstni (birds, wild animals, flowers, triangles) served also as personal signs of owners, if imprinted on wax after text of document, they countersigned the transaction. (Pushkareva)

Metalwork was highly developed in Kiev. Embossing, engraving, stamping, casting, granulation, filigree, and enameling were widespread skills. (Stamerov)

See Jewelry for more information.

Navesni Ornaments - removable collars, cuffs, etc.

-

Zarukavya – a removable cuff generally made of a narrow piece of expensive fabric, often

embroidered. Could be worn with the rubakha. (Kireyeva)

Cuffs – removable ornaments for the wrist on ceremonial occasions. Made to match the pectoral. See below. (Stamerov)

Ozerelya – a broad circular removable collar, richly ornamented even with pearls or gems,

buttoning in the back, worn over the outer rubakha for holidays, but perhaps only by

royalty and the highest nobility. (Kireyeva)

Pectoral – a wide round circular collar laying around the neck to cover the upper chest,

shoulders and upper back for ceremonial occasions. Generally made of a golden fabric,

with metal embroidery, pearls and even gemstones. (Stamerov)

See Accessories for more information.

Belts and purses

-

Belts for the rubakha, required for decency, were made of fabric or leather 1.5 to 2 cm

wide. They were not cinched in tightly, and were generally fastened with metal buckles

that were round or lyre-shaped. (Stamerov)

Kalita – the bag-purse hung from a man’s belt. (Kireyeva)

The purse – a leather pouch or brocaded bag, was tied to the belt since garments did not

have pockets. Commoners would wear a knife and simple drawstring pouch at the belt.

(Stamerov)

See Accessories for more information.

Footwear:

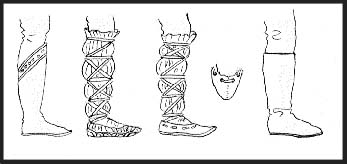

Peasants and poor villagers had bast shoes and postoli (with onuchi) to wear. Prosperous

villagers, townmen and nobles preferred to wear boots. (Stamerov)

Peasants and poor villagers had bast shoes and postoli (with onuchi) to wear. Prosperous

villagers, townmen and nobles preferred to wear boots. (Stamerov)Onuchi – foot and lower leg wraps made of long strips of linen fabric, up to 2 meters long. (Kireyeva and Stamerov)

Boots – worn by wealthy peasants and the nobility. High boots without heals were made of leather of various colors. Boots with heels appeared in the 14th century. (Kireyeva)

Common boots were usually short in the toes and high in the back with a knee-high, soft boot top that was cut straight across. The boots of the ruling class could have turned up toes. Some boot-tops were cut at an angle - higher in front than in back. None of the boots had heels. They were made of hide colored balck, brown and dark yellow. The nobility could also afford red, violet, dark blue or green, with tooling and embroidery in stripes, circles and dots. (Stamerov)

Lapti – traditionally woven of bast (from tree bark) and bound to the feet with lacing threaded through eyelets in the sides. These laces extended up to the kneed to bind up the onuchi. (Kireyeva and Stamerov)

Shoes – porshni-postoli made of a single piece of untanned hide might be worn instead of the bast shoes. The hide was turned up at an angle in the front and sewn to form a toe, then on the back and sides the leather was turned up and held in place by straps threaded through holes in the hide. These straps were then bound around the shins. (Stamerov)

See Footwear for more information.

Comments and suggestions to lkies@jumpgate.net.

Back to Men's Clothing or Early Rus Clothing.

Back to Russian Material