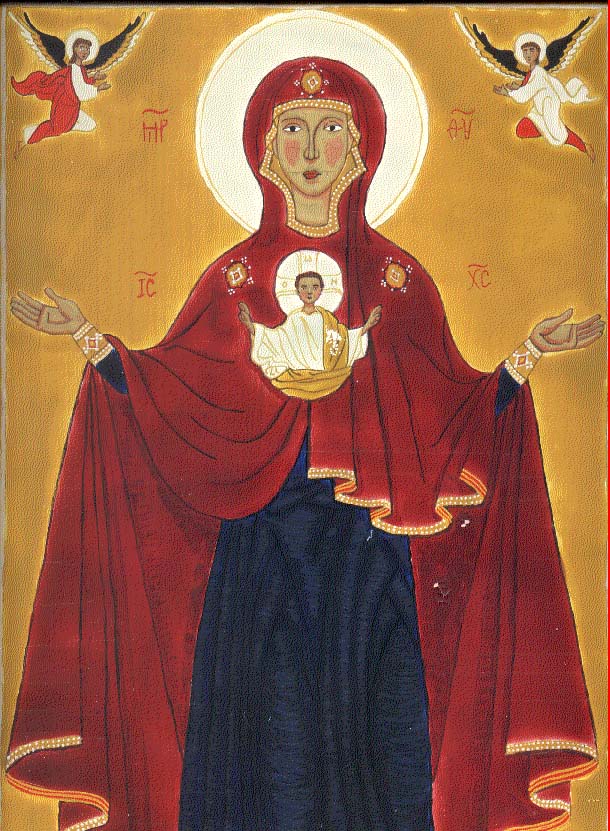

The Virgin Great Panagia

History 421

Semester Project

November 30, 1994

(revised July 1998 and July 2002)

Icons are an important part of Eastern Orthodox rites, and the conversion of

Rus' coincided with the peak of the Byzantine development of icons. The

Virgin Mary, known most often as the Mother of God, is one of the most

popular subjects for icons - second only to Christ. Her role as Mother of

God and intercessor for mankind is central to Orthodox belief and is

emphasized by the fact that the Feasts Tier of an iconostasis (altar screen)

depicts events in her life, as well events in her Son's life. (Kyzlasova,

1988.) In addition, there are many different icon types depicting the

Virgin.

Icons are an important part of Eastern Orthodox rites, and the conversion of

Rus' coincided with the peak of the Byzantine development of icons. The

Virgin Mary, known most often as the Mother of God, is one of the most

popular subjects for icons - second only to Christ. Her role as Mother of

God and intercessor for mankind is central to Orthodox belief and is

emphasized by the fact that the Feasts Tier of an iconostasis (altar screen)

depicts events in her life, as well events in her Son's life. (Kyzlasova,

1988.) In addition, there are many different icon types depicting the

Virgin.

Of these, one of the most ancient and revered is the Virgin Great Panagia. This icon shows the Virgin standing in a position of prayer with her hands spread in supplication as in the Virgin Orans, but with the Christ child depicted on her chest as in the Virgin of the Sign. (Rice, 1974.)

![]() The icon of the Virgin of the Sign is placed in the center of the Prophets

Tier of an iconostasis as the representation of the fulfillment of the Old

Testament prophesies, particularly Isaiah's prophesy from Isaiah 8:14,

"Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; behold a virgin shall

conceive in the womb, and shall bring forth a son, and thou shalt call his

name Emanuel." This connection with Isaiah is so strong that some

iconostases omit Isaiah from the Prophets Tier. The presence of the angels

in the icon emphasizes the Virgin's exalted position - above the angels.

(Ouspensky, 1982.) The three fibula, the golden jeweled emblems on the

Virgin's shoulders and forehead, symbolize her chastity before, during and

after being with child. Icons of the Virgin of the Sign reproduce an

original Byzantine icon kept in the church of the Blachernae at

Constantinople, where it was venerated as the palladium of the imperial

house and defender of the walls of the city. Such icons became widespread

in Russia in the 12th and 13th centuries and were apparently also regarded

as granting protection to princes and cities. (Maslenitsyn, 1973.) One

Russian version, of Novgorodian workmanship, was so revered that it was

carried into Novgorod's battle with the Suzdalians of Andrey Bogolyubsky.

This even was then depicted by the Novgordians three centuries later to

invoke aid against the attack of Moscow. (Rice, 1974.)

The icon of the Virgin of the Sign is placed in the center of the Prophets

Tier of an iconostasis as the representation of the fulfillment of the Old

Testament prophesies, particularly Isaiah's prophesy from Isaiah 8:14,

"Therefore the Lord himself shall give you a sign; behold a virgin shall

conceive in the womb, and shall bring forth a son, and thou shalt call his

name Emanuel." This connection with Isaiah is so strong that some

iconostases omit Isaiah from the Prophets Tier. The presence of the angels

in the icon emphasizes the Virgin's exalted position - above the angels.

(Ouspensky, 1982.) The three fibula, the golden jeweled emblems on the

Virgin's shoulders and forehead, symbolize her chastity before, during and

after being with child. Icons of the Virgin of the Sign reproduce an

original Byzantine icon kept in the church of the Blachernae at

Constantinople, where it was venerated as the palladium of the imperial

house and defender of the walls of the city. Such icons became widespread

in Russia in the 12th and 13th centuries and were apparently also regarded

as granting protection to princes and cities. (Maslenitsyn, 1973.) One

Russian version, of Novgorodian workmanship, was so revered that it was

carried into Novgorod's battle with the Suzdalians of Andrey Bogolyubsky.

This even was then depicted by the Novgordians three centuries later to

invoke aid against the attack of Moscow. (Rice, 1974.)

![]() The most well-known surviving representation of the Virgin Great Panagia was

found in 1919 in an old storeroom at the Monastery of Our Savior in

Yaroslavl by an expedition led by I.E. Grabor. Its exact provenance is

difficult to determine because it, like the vast majority of Russian icons,

was unsigned.

The most well-known surviving representation of the Virgin Great Panagia was

found in 1919 in an old storeroom at the Monastery of Our Savior in

Yaroslavl by an expedition led by I.E. Grabor. Its exact provenance is

difficult to determine because it, like the vast majority of Russian icons,

was unsigned.

Three schools of Russian icon painting developed before the Mongol invasion - in Kiev, Novgorod and Vladimir-Suzdal. The Kievan school was probably the most closely linked to the Byzantine tradition, but all its icons have been lost except, perhaps, for the Virgin Great Panagia. Some scholars see unmistakable Kievan stylistic ties in this icon and so believe that it was painted in Kiev in the 12th century. (Alpatov, 1974. Onasch, 1977. Rice, 1974.) The catalogue of the Tretyakov Gallery, the present home of the Virgin Great Panagia, also places it in Kiev and suggests that it was painted around 1114 by Alipy, one of the few icon painters who has been remembered by history and one of the first native Russians to paint icons. (Rice, 1974.) Some claim that it shows distinct similarities to the equally impressive representation of St.. Demetrius of Salonica which was found to have the cipher of Grand Prince Vsevolod III (1176-1212) indicating that it was painted for him and giving a possible origin and date for the stylistically similar Virgin Great Panagia. (Rice, 1974.) Another argument is that it resembles Northeast Russian art under Vsevolod III, and perhaps was the 13th century work of a Vladimir Master commissioned by Vsevolod's son, Constantine the Wise, for the Cathedral of the Assumption in the royal palace of Yaroslavl. From there it would have found its way into the storeroom of the Monastery of Our Savior, where it was found in 1919, after the Cathedral of the Assumption burned down in 1501. (Maslenitsyn, 1973.) But whatever its origin, the majestic beauty of the Virgin Great Panagia has inspired many icon painters, including myself.

All known representations of the Virgin Great Panagia in Russian art are

associated with royal princes (Maslenitsyn, 1973) and so I imagined that my

icon was also painted for a royal prince - in a more outlying principality

(to account for the unskilled execution). I also decided that my icon would

represent the style of the 13th century soon after the completion of my

model, the Virgin Orans - Great Panagia of Yaroslavl. By this time, the

development of a uniquely Russian style had already started. Bright,

exuberant pure tones were starting to be seen in touches, added to the muted,

dark Byzantine palette. Accordingly, the colors I used were similar to

those used in the original Virgin Orans Great Panagia, but slightly more

exuberant, expressing a greater native Russian influence. Cinnabar red was

a favorite color, particularly by the 13th and 14th centuries (Alpatov,

1974) when my icon would have been painted, and so I included that color in

the archangels' robes, the lettering and the carpet. I chose to depict the

Christ child blessing with both hands and without a mandorla (a circle

representing heaven, Divine Glory and Light). The Christ Child can also be

depicted giving a blessing with only one hand, holding a scroll in the

other, inside a mandorla. I slightly modified the ornamentation of the

Virgin's fibula, cuffs and robe border. The archangels in the upper corners

were adapted from a 17th century icon of Christ Pantocrator with the shape

of their wings changed to make them closer to the shape shown in the early

Russian icons.

All known representations of the Virgin Great Panagia in Russian art are

associated with royal princes (Maslenitsyn, 1973) and so I imagined that my

icon was also painted for a royal prince - in a more outlying principality

(to account for the unskilled execution). I also decided that my icon would

represent the style of the 13th century soon after the completion of my

model, the Virgin Orans - Great Panagia of Yaroslavl. By this time, the

development of a uniquely Russian style had already started. Bright,

exuberant pure tones were starting to be seen in touches, added to the muted,

dark Byzantine palette. Accordingly, the colors I used were similar to

those used in the original Virgin Orans Great Panagia, but slightly more

exuberant, expressing a greater native Russian influence. Cinnabar red was

a favorite color, particularly by the 13th and 14th centuries (Alpatov,

1974) when my icon would have been painted, and so I included that color in

the archangels' robes, the lettering and the carpet. I chose to depict the

Christ child blessing with both hands and without a mandorla (a circle

representing heaven, Divine Glory and Light). The Christ Child can also be

depicted giving a blessing with only one hand, holding a scroll in the

other, inside a mandorla. I slightly modified the ornamentation of the

Virgin's fibula, cuffs and robe border. The archangels in the upper corners

were adapted from a 17th century icon of Christ Pantocrator with the shape

of their wings changed to make them closer to the shape shown in the early

Russian icons.

The question of whether my icon represents a primitive 13th century version of the Kievan or Yaroslavian (Vladimir) icon schools depends on the outcome of the controversy over the provenance of the original Virgin Orans Great Panagia. My own suspicion is that trying to separate such early Russian icons into different schools is rather futile. The very young art of Russian icon painting probably hadn't developed enough by this time to be completely separate from the original Byzantine tradition, much less demonstrate separate, distinct Russian traditions, as the controversy itself demonstrates. Therefore, I would prefer not to try to name a stylistic school for my icon.

Illustrations are my original work except:

Our Lady of the Sign, Yaroslavl, 17th century, Yaroslavl Art Museum.

Our Lady the Great Panagia (Orans) from the Monastery of Our Savior, Yaroslavl, 12th or 13th century, now in the Tretyakov Gallery. Image courtesy of the Yaroslavl Art Museum from the CD, Yaroslavl Icon Painting.

Bibliography

Return to Russian Materials

Return to homepage