Jewelry in Early Rus

Updated 4 April 2007

In the 9th-13th cent., the ancient Russian costume was supplemented by multiple decorations of metal, stone, glass and other materials. The heads of women and maiden-bride’s were decorated with metal ornaments which were sewn to the headdress, hung down, entwined in the hair, and passed through ear lobes. These ornaments originally were in special forms for each tribe, later under the influence of the cities, appeared “extra tribal” forms of ornament (mainly with different forms of assumed [напускными] metal beads) and the specifically urban ornaments, kolti. Besides the ornaments (“temple rings”, as they’re called by archaeologist), the head could be decorated with a metal venchik [венчик], on this same headdress was sometimes embroidery of small glass beads, bicera [бус vs. бисера]. (Rabinovich, 9-13th) See Women's Headdresses.

In the 9th-13th cent., on the neck were worn metal hoops [обруч], grivni or ozherl’e of metal, stone and glass beads, the favorite set of which was also originally unique for each tribe. The hypothesis of M. B. Fekhner was that the difference in the set of beads worn was not ethnic, but chronological in character appears bad to us (Fekhner, 1959; Rabinovich, 1962). In the composition of ozherl’e are met both bronze little bells, which are also sometimes sewn on clothing as buttons. The embroidery of the standing collar of the rubakha and the buttons fastening the collar served also as decorations. On the wrist were worn different types of hoops [обручи], bracelets, and on the fingers, perstni [перстни, rings]. These defined the set of ornaments of ancient Russian women. In distinction from neighboring Finno-Ugric and Letto-Lithuanian peoples, the Slavs did not know either an abundance of different types of noisemaking ornaments, or hoops decorating the shin of the leg. Temple ornaments were characteristic for all Slavs. L. Niderle noted that, in comparison with their neighbors, Slavic women were not so richly decorated, but their decoration was distinguished by elegance and fine craftsmanship (Niderle, 1956, p. 242-247). (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In the 9th-13th cent., the costume of ancient Russian men was significantly less decorated than that of women. For the poor person ornament was limited to buckles and plaques - the “set” for the belt. More prosperous peasants wore also a hat with a sewn on metallic decorations, for which, in the 12th to 13th centuries, was often used crosses; in such cases the cross was by no means to be considered symbols of Christian religion, in that they were found in pagan burials (Latysheva, 1954, p. 52-53). Significantly more rich was the set of men’s ornament in the princely-boyar environment. The princely otrok-courtier sometimes wore on the neck a grivna. Gold grivni of a certain type were a mark of distinction or favor from the prince (PVL, I, p. 95). The long upper clothing of the rich person could have, on the chest, paired figured fasteners (Rybakov, 1949, p. 38-39), and the cloak thrown over the shoulders, beautiful buckles. It is especially necessary to note the precious regalia of the prince, barmy, in that time presenting itself as a chain of gilded silver or gold medallions with enamel ornament (Mongajt, 1967, Fig. 13-14). (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In the 13-17th century there occured a fundamental change in decoration. The ancient colorful tribal costume with its temple rings and simple women, peasants and city dwellers, begand to wear rather less ornament. After the ancient style, one can see in embroidery of headdressa nd nonmetallic decoration - pushkakh (fluffy white down ornaments), kudryakh (curls?). But wealthy women continued to have a multitude of valuables. The written sources are sprinkled with records of rings (perstni), bracelets (obruchi), necklaces (monsity), and earrings (sergi). Some of these items are preserved in museums. (Rabinovich, 13-17th c.)

In the 13-17th cent. on the neck women wore the monisto, a necklace in the modern sense of the word, and sometimes also the grivna. The grivna for men is not recorded in the 13-17th cent. The monisto was made of beads, more or less valuable, depending on the fortune of the wearer. Zanoski, little gold chains for crosses, and simple gold chains (tsepki) were worn on the neck. On the wrist were worn bracelets (obruchi), on the fingers were worn rings (perstni). Rich women wore on every hand several bracelets and rings. Men's gold rings were called zhikovina or napolok. The ryasy, strands of pearl grains, decorated women's headdress. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

One wealthy late 15th cent. Russian woman owned the following: 2 earrings with ruby/sapphire, and another... 3 earrings, 2 ruby/sapphire, and another... a large gold necklace and 3 gold bracelets... a necklace on cord/braid... 2 gold bracelets... and 3 gold bracelets... 17 gold rings. We see in other similar records from late period a great abundance of pearled items, indicating the relatively low value of pearls in the Russian north. In marriage records of ordinary peasants of the 16th cent. are only recorded silver earrings. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

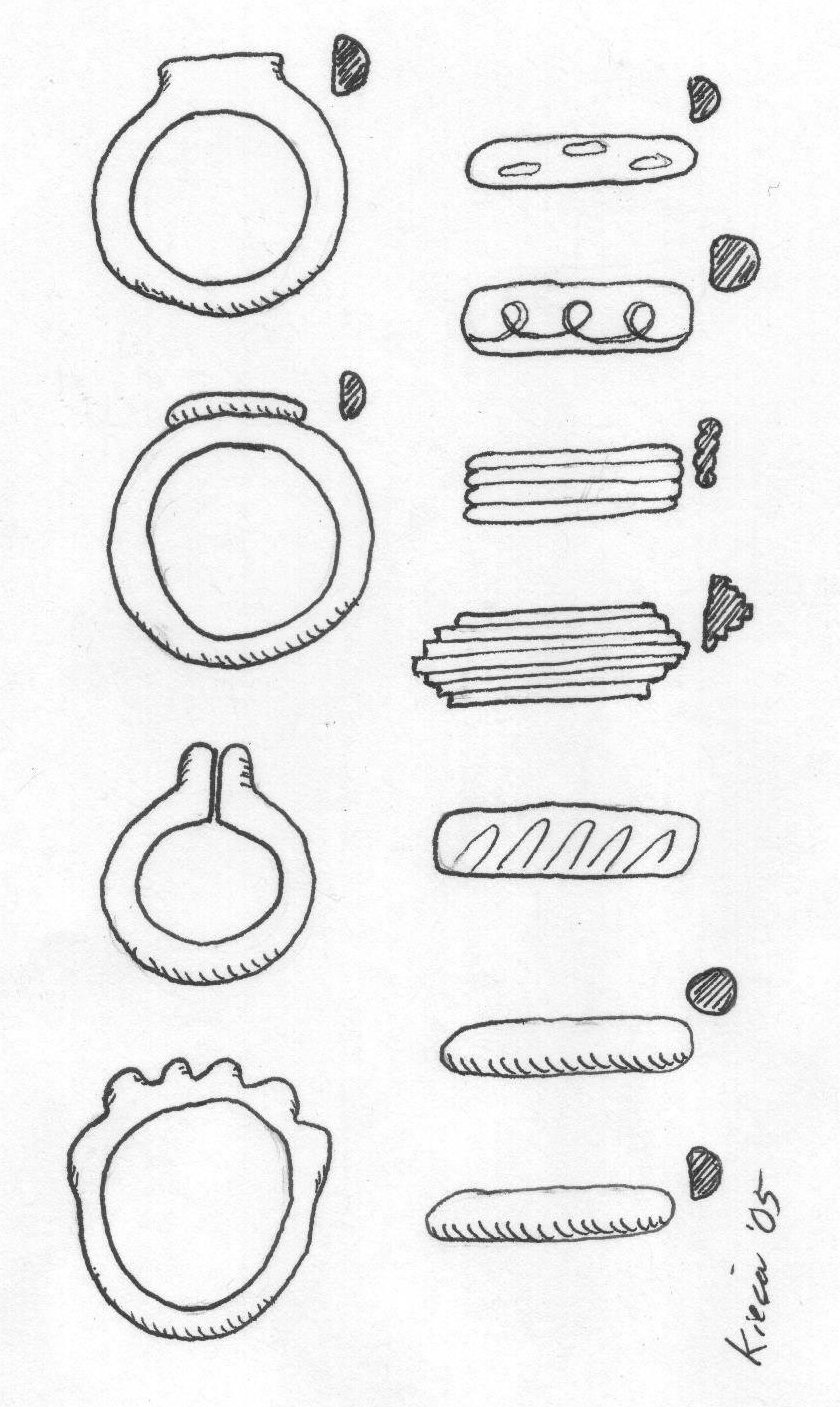

Earrings:

-

There is some confusion about the role of earrings in women's attire.

According to Stamerov, earrings were seen often, especially the

"three-beads" worn by noble men in one ear. But Pushkareva says that

earrings were not particularly common from the 10th-13th centuries. These

are not necessarily contradictory. Pushareva was referring specifically to

women, while Stamerov was talking more generally and was, perhaps, referring

more to a time after the 13th century. (Stamerov) and (Pushkareva97)

Women's earrings are met with much more rarely than temple rings, kolti and neck ornaments in early written sources and archeological finds. One of the types of women's earring - in the form of a question mark - was discovered in Novgorod and dated to 13-15th cent. Women's earrings are mentioned in the will of a certain Volotski princess. And an old princess indicated in her will that three small stones from her earring - two ruby/sapphires and one lal (ruby) - were to be sewn into a smart hat for son Ivan; while the earring, itself, without the stones, she set aside for her future daughter-in-law, while for the wife of her oldest son - also a pair of earrings with ruby/sapphires and lalami (rubies), stones from which buttons of ozherel'ya (necklace or collar) of son. (Pushkareva89)

In the 13-17th cent. earrings appeared as gold or silver rings or small hooks with ornaments of metal beads or, more often, valuable stones. Among types of earrings are names "odintsy", dvojny" and "trojni", respectively, single, double and triple refering to the number of pendants hanging from the ring. Even men wore one earring. This was an ancient custom tracing back to the 10th cent. In 1356, Moscow prince Ivan Ivanovich willed to his sons one earring with pearls each. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

The popularity of earrings in 15th cent. Novgorod and across all Russia proves that the women’s headdress was worn in such a manner that the ears remained uncovered. Icons give examples of how it is possible to cover hair but to leave the ears uncovered to show the earrings. These images also prove that the church considered such a liberty permissible. About the Novgorod women a proverb was even preserved: "To a well to get water, without putting on gold earrings, do not go". (Bykov/Kuzmin)

Three-pendant earrings [ser'gi-trojchatki] are made of a round, not closed, shvenzy-ring and three suspension brackets which are made from short, straight metal rods, wound on the shvenzy, and strung with various combinations of cast metal cylinders, decorations of false granules, pearls, beads, drilled semi-precious stones, and mother-of-pearl grains. Trojchatki received a wide circulation since the XVth cent. (Bykov/Kuzmin)

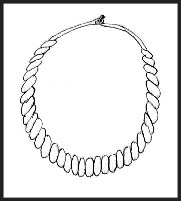

Neck Ornaments:

-

Neck ornaments were popular with women of all classes and, most of all, glass

beads. (Pushkareva89)

In the 13-17th cent. on the neck women wore the monisto, a necklace in the modern sense of the word, and sometimes also the grivna. The grivna for men is not recorded in the 13-17th cent. The monisto was made of beads, more or less valuable, depending on the fortune of the wearer. Zanoski, little gold chains for crosses, and simple gold chains (tsepki) were worn on the neck. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

-

They consist of hundreds of varieties, each with its unique ornament, form,

and coloring. Set apart are four types of glass bead, worn by ancient

Russian city-dwellers: 1. blue, black, light-green glass with intricate

"eyes"; 2. many-layered glass small sticks/wands, which were divided and

pierced; 3. hollow beads; 4. and finally polyhedra/many-sided beads carved

of hardened solid glass, as of stone. (Pushkareva89)

Beads of many-colored "rublennogo bicera" (chopped beads) had the greatest prevalence. (Pushkareva89)

Ibn-Fadlan, describing his visit on the Volga in the 10th cent. noticed that wives of Rus especially liked green beads. He claimed that husbands went broke, paying 15-20 coins of silver for each green bead. Among kurgans, finds of green beads are rare; in modest burials are come across blue, turqoise, yellow and striped. In the environment of the nobility, bead ornaments are prevalent, combining beads of various materials (for example, gold hollow beads, pearl grains, and also made/turned-on-lathe of valuable stones). A Volotskaya princess bequeathed eight such gold "pronizok" ("pierced") to her children. (Pushkareva89)

The grivna is the very oldest form of ornament and widely used among the

peasants. Grivny (named like the money) were twisted or flat chokers made

of bronze, alloys or silver or massive hoops of twisted jute or heavy

breaded wire. These were mostly worn by men according to Stamerov.

(Pushkareva97) and (Stamerov)

The grivna is the very oldest form of ornament and widely used among the

peasants. Grivny (named like the money) were twisted or flat chokers made

of bronze, alloys or silver or massive hoops of twisted jute or heavy

breaded wire. These were mostly worn by men according to Stamerov.

(Pushkareva97) and (Stamerov)

In distinction from "demokraticheskikh" beads, metal hoops - grivny - which were worn as neck ornaments in 10-13 cent. and in part later, appeared as the property only of prosperous peasants and city-dwellers. Many grivny preserve traces of repairs - a sign that they represented well-known value. The most valuable grivnami were bilonovye (alloy of copper and silver); while the most wide-spread were copper or bronze, sometimes with traces of silver coating. Different types included drotovye (javelin?), round wire, plastinchatye (metal plate?) and twisted grivny. Each type corresponded to a definite area of spread. For example, near Ladozhski Lake, twisted and drotovye grivny are found, while women of North-East Rus wore mainly twisted grivny. Twisted/braided grivny invariably are met on miniatures depicting scenes of weddings. In the Nikonovski chronicle can be counted 23 depictions of grivny. Neck grivny preceded later metal ornaments of the type of ozherelij, although they continued to exist as holiday ornaments of noble women even in 16th cent. (Pushkareva89)

-

Ozherel'ya (from "zherlo" - neck) necklaces of pearl grains, gold

badges/plates and similar valuables are well-known both by the assembly of

material and by the chronicle memorials. Volinski prince Vladimir

Vasilkovich "pobi and pol'ya" in ingot of necklace "of his wife and mother".

Ozherel'ya with "pearl seven-foot-measure" and "great ruby/sapphires" are

mentioned in will of Verejski prince Mikhail Andreevich, and "ozherel'noj of

pearls" - in the will of a Volotskoj princess. (Pushkareva89) Other

necklaces were complex plaited chains and pendants with little bells or

religious medallions. Small crucifixes on chains or cords were a growing

custom. (Pushkareva97) and (Stamerov)

The body cross, krest' telnik, was worn around the neck laying against the skin and was "never" taken off.

The term ozherl'ya is frequently used to refer to the highly decorated collars as well. See the Accessories Page.

-

Very valuable and expensive neck ornaments for women of priviledge classes

were chains (tsepi). Among these appeared kol'chatye (of rings), and

"ognichatye" (of oblong "ogniv"), and chernenye (black? niello? - they were called

"vranye tsepi" - raven chains), and also in form of trihedron prisms. The

beginning of 13th cent. dates the first mention of gold chains as a women's

ornament in the Ipatevski chronicle. In birchbark letter No. 138 (second

half of 13th cent.) are named two chains, valued at two rubles. (Two rubles

in Novgorod in the 14th cent. could buy 400 squirrel hides.)

"Khrest'chatuyu" gold chain (its drawing showed linking tiny golden crosses,

krestikov) was given by Kashinski princess Vasilisa Semenovna to Grand

Prince Vasili Dmitrievich. (Pushkareva89)

-

Among hanging ornaments of nobility were known also medallions.

They were made from silver or gold, decorated with "partitioned" enamel,

grains, and skan'yu (?). Since the 12th cent. medallions of cheaper

alloys began to be produced in imitation of the more expensive, cast in

similar forms. (Pushkareva89)

A zmeevik (medalion) was found in a layer dated dendrochronologically to 1313-1340. It is cast from a tin-llead alloy in a bilateral foundry form. On each side of the waist-length figure of the Mother of God, is located a backward inscription: on the right - M, on the left - PY. The image on the face side recalls a zmeevik from the collection of the Hermitage, dated to the XVth century. However, on the Novgorod zmeevik, instead of an inscription, along the edge there is a pattern of two rows of triangles and concentric circles. (Bykov/Kuzmin)

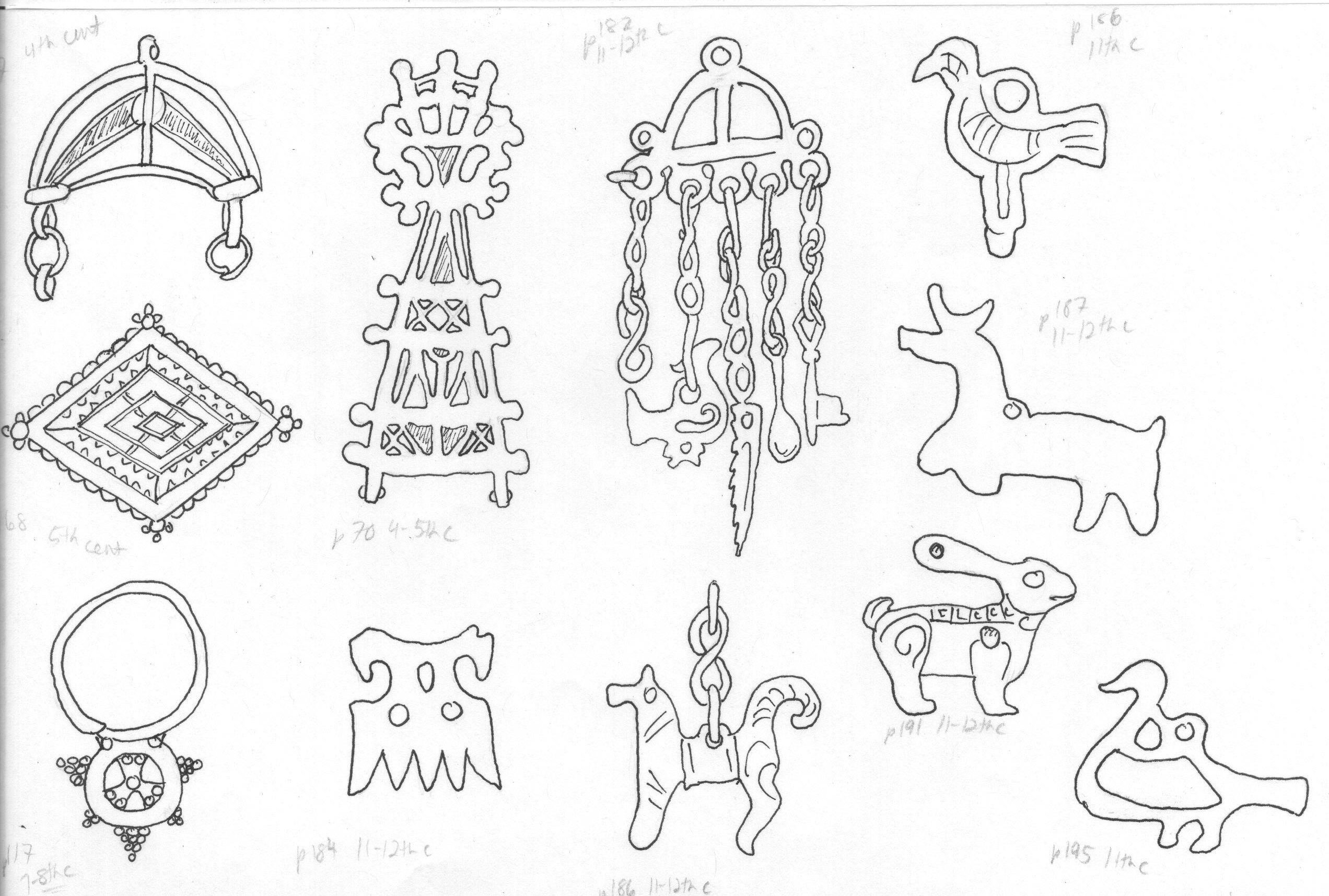

Priveski:

They were worn on long cords or "chepkakx" (small chains), fastened to the dress on the chest (as shown by Kolchin) or on the belt. Priveski were made of silver, copper, bronze, bilona (alloy of silver and copper). (Pushkareva89)

By outward contour they are separated into zoomorphic forms, and those reproducing objects of life and symbolizing plenty (spoons, keys, combs, etc.) or wealth (small knives, hatchets). The later - together with swords - were symbols of the worship of Perun. Also worn were small bells, noise-making priveski, needle cases, and also geometric priveski (circles, moons, little crosses, rhombi, club/clover-shaped, spear-shaped, etc.). (Pushkareva89)

At the present time some 200 types of privesok are known; several of these appeared among the Slavs as a result of borrowing from neighbors, for example from Ugro-Finns. (Pushkareva89)

One of the favorite privesok-amulets of ancient Russian women was the little horse with long, outstretched ears and curled-up-in-a-ring tail. The horse was a symbol of goodness and luck, fidelity and friendship, connected with the cult of the sun and in preveskakh, it was invariably surrounded by little circles - solar symbols. Besides horses frequently were worn stylized portrayals of water birds, personifying life-giving property of water, and sirens ("mermaids" - symbols of domestic prosperity.). Many Novgorodians wore on the belt on leather laces ob"emnye ("three-dimensional" - hollow inside) depictions of animals with one or two heads, tails twisted in a spiral and small chains instead of legs. (Pushkareva89 and 97)

Everyday priveski-amulets were produced for the most part in the countryside and were part of the costume of rural residents. The countryside preserved the devotion to pagan cults longer than the city, therefore in rural burials among privesok often appear moons and crosses, connected with the ancient pagan deity Yarilo. Part of costume of the ancient Russian nobility were objects analogous to the priveskam-amulets of peasants and city-dwellers. For example, in the will of prince Dmitri Ivanovich (1509) mentions "mayalki (noise-making priveski) with ruby/sapphire and pearls". (Pushkareva89)

Bells:

-

Favorite ornaments of both city-dwellers and peasants were also small bells

with various splits/sections. As a typical ornament of women's costume they

existed right up to the 15th cent, while the above-named privesok existed

only to 13th cent. Small bells were worn in complex with other priveskami

and and in composition of beads, sometimes hung from neck grivny. They

could be ornaments of ventsa or kiki, and could be braided in hair on small

hanging straps. Small bells were frequently used even in the capacity of

buttons. But for the most part this was a traditional hanging ornament of

the belt, on sleeves, and leather waist/belt purses. (Pushkareva89)

According to the beliefs of the eastern slavs, bells and other noise-making priveski were considered symbolic representations of the god-"thunder", guarding people from evil spirits and unclean forces. (Pushkareva89)

-

Decorative buckles, clasps, pins and fibulae were used to fasten blouses/shirts at

the neck, attach pendant and amulets to dresses, and to hold household

implements such as keys, knives, flint and scissors onto belts.

(Pushkareva97)

Fibuli were a part of womens' attire especially for parades/processions. They were made from iron, tin-lead alloy, copper, bronze, silver. One of the first mentions of fibulax is kept in "Tales of Bygone Years" under 945, but the largest number of archeological finds fall on strata of 10-12th cent. (Pushkareva89) Clasps and pins for formal occasions could be made of gold, silver, bronze or alloys with precious stones. (Pushkareva97)

In one grave usually is found only one large preveska-clasp, more rarely - two. They wore them either on shoulder, or on chest (they fastened the upper, draped clothing of cloak and cape type). With small fibulami ancient Russian women fastened sorochki at collar, fastened amulets and preveski to belt, and also household objects: keys, kresala (?), small knives. Fibulami could also fasten ornaments to women's headdresses. (Pushkareva89)

Up to 10th cent. clasps-fibuli were only large and massive, but later, in the 14-15th cent., light and small predominated. In all centuries this type of ornament was embellished richly, depending on ethno-national region, degree of skill of kovshik (maker?), of precision (? chekanshckikov), and other similar causes. (Pushkareva89)

Pins had the same structural-functional meaning that fibuly had in women's outer costume - but were characterisic of costume only of noble city-dwellers. Two identical in form and size clothing pins with long bar/pivot and large "slit" head, united with a small chain, supported the vcstyk (in-joint?) edge of the cloak. (Pushkareva89)

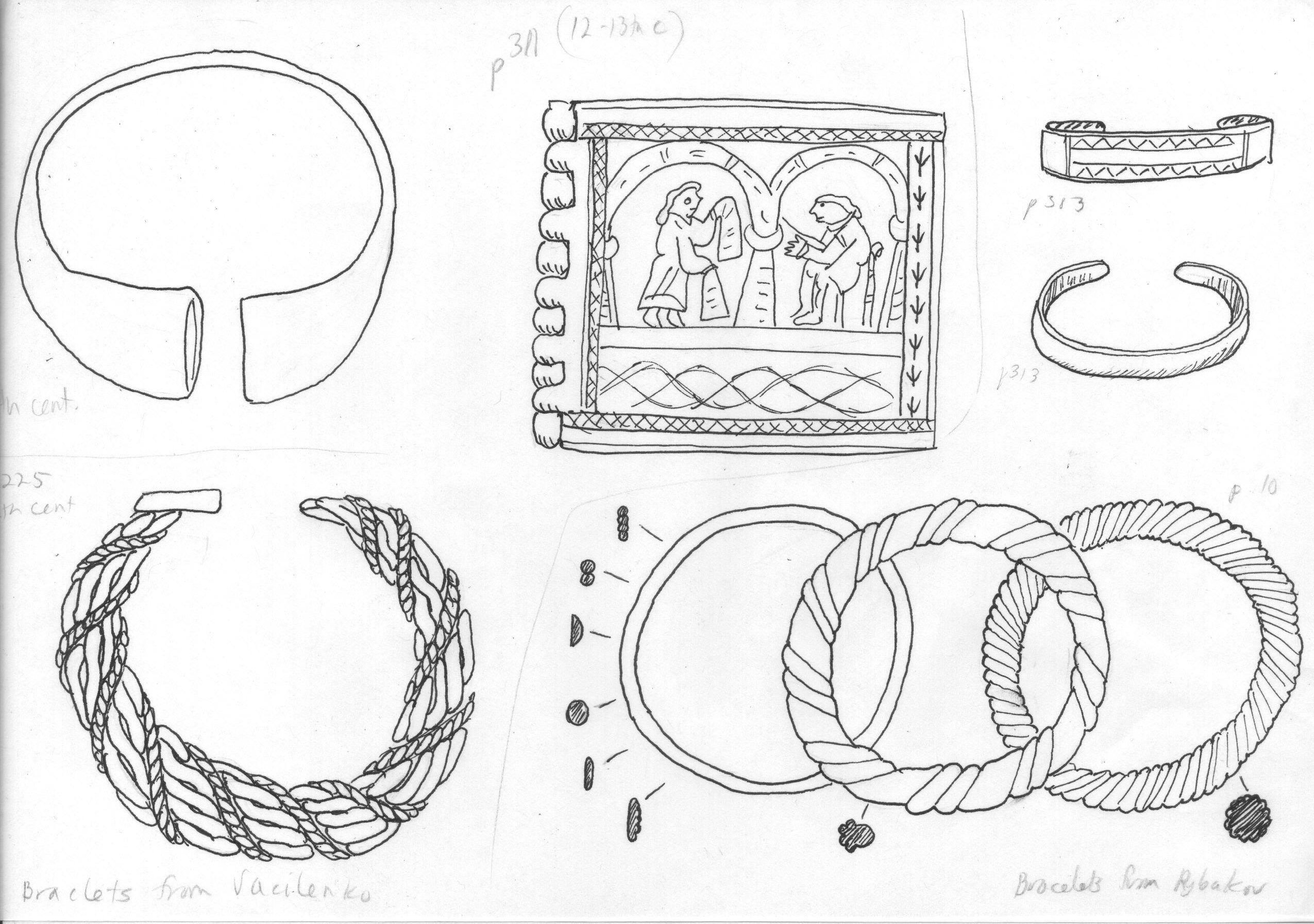

Bracelets:

Rubakha sleeves were sometimes finished with a zarukavya/poruchiv/naruchami, narrow ornamented cuffs which helped hold up the extra long sleeves. The sleeves might also be fastened at the wrist with bracelets. Women's bracelets were made of metal, twisted wire and patterned disks, glass rods, glass ornaments and beads, metal, wood, leather, or birchbark. (Kireyeva) and (Stamerov) and (Pushkareva97 and 89)

See also Cuffs on the Accessories Page.

Ancient Russian city dwellers gladly wore glass bracelets. Their fragments are found among excavations of ancient layers (beginning 10th cent.), but most often of all they appear in the little cities of the 11-13th cent. where the quantity of such finds is numbered in the thousands. One finds light blue, blue, green and yellow fragments of bracelets, which give an idea about the principle of their creation: glass sticks bent in ring, core/rod/hearts painted and sometimes twisted with metal or glass filaments of a contrasting color. (Pushkareva89)

Glass bracelets were mainly the ornaments of city-dwellers, while metal adorned both city dwellers and peasants. Most often of all are found copper and bronze manufacture, more rarely silver and bilonovye (silver/copper alloy). Gold plastinchatye (metal plate?) bracelets often were worn on the forearm near the elbow joint. Many bracelets were worn over the sleeves of sorochki/rubakhas. Strikingly great in number are their variety: drotovye ("javelin"), twisted, pseudotwisted (cast to imitate twisted bracelets), woven, plastinchatye (metal plate?), lad'evidnye (rook/castle?/boat? shaped), uzkomassivnye (literally "tight/narrow massive" - in form of a stretched-across-wrist rhomboid or oval) and others. Specific folding bracelets of bilona (silver/copper alloy), lead with tin, silver, in such cases gilded, were only for city.

In the 13-17th cent. on the wrist were worn bracelets (obruchi), on the fingers were worn rings (perstni). Rich women wore on every hand several bracelets and rings. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

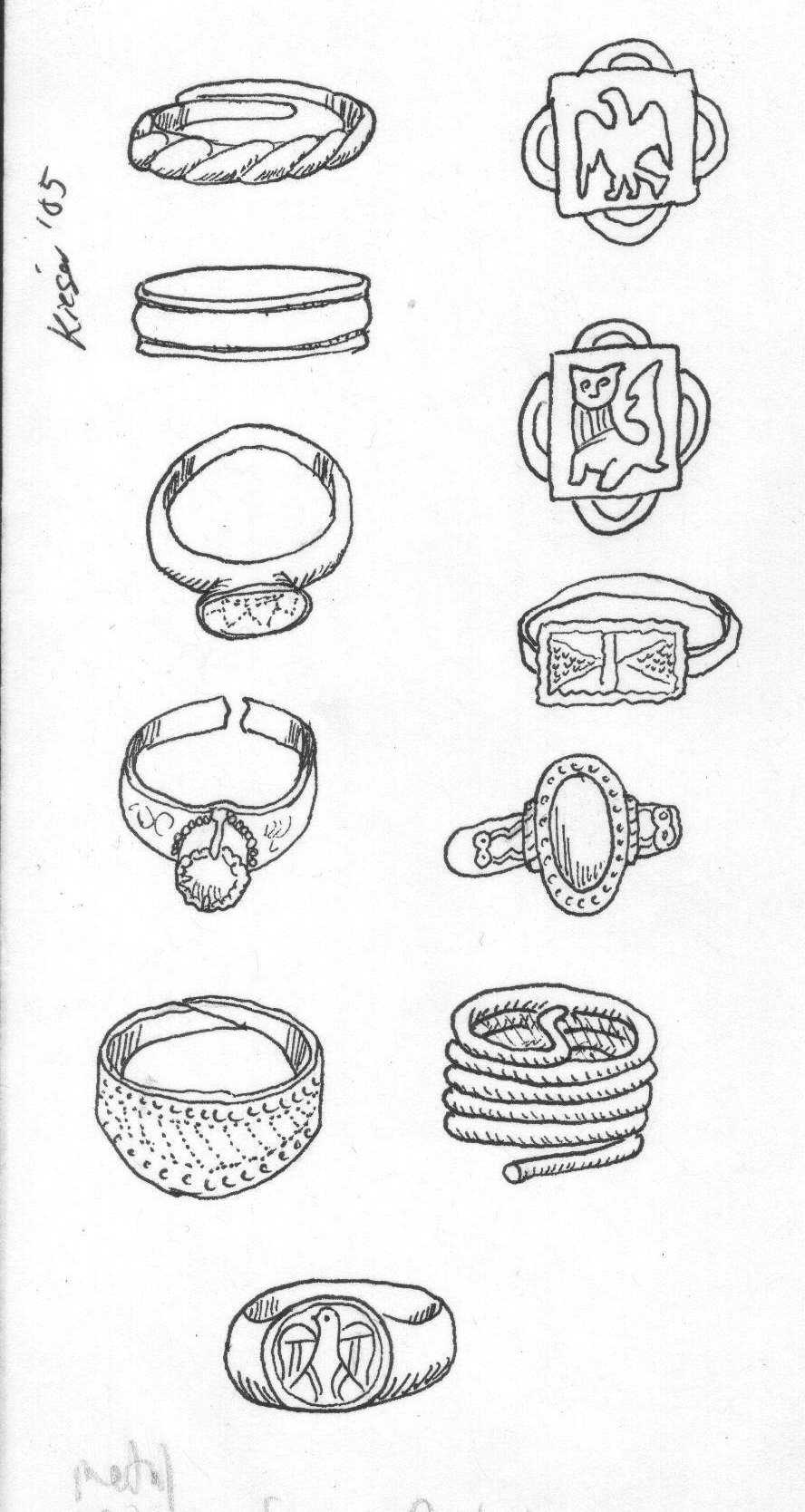

Rings:

In the 13-17th cent. on the wrist were worn bracelets (obruchi), on the fingers were worn rings (perstni). Rich women wore on every hand several bracelets and rings. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Comments and suggestions to lkies@jumpgate.net.

Back to Early Rus Clothing.

Back to Russian Material