Footwear in Early Rus

Updated 4 April 2007

Footwear:

Footwear varied greatly between social classes. (Pushkareva97)

One of the first mentions of "sapozek" (boot) and "laptex" (similar to

modern word for sandal) is contained in the Lavrent'evski chronicle under

the year 987. (Pushkareva89)

Footwear varied greatly between social classes. (Pushkareva97)

One of the first mentions of "sapozek" (boot) and "laptex" (similar to

modern word for sandal) is contained in the Lavrent'evski chronicle under

the year 987. (Pushkareva89)

In the 9th-13th cent. the most widespread material for shoes was wood bark and bast for lapti. But by the 10th cent., city dwellers and well-to-do peasants usually used leather, rawhide or tanned. The leather industry was centered in the city and, in the 9th-13th cent. had not yet separated from the profession of cobblers. In the villages, leather production was still a household activity. Ancient Rus had both thick leather, yuft', and more thin leather, opoiku. They used skins of cattle, horses and goats. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Shoes, as already stated, were made in the 9th-13th cent., of bark, leather, and maybe also fur (Fig. 11). Neither wooden carved-out shoes, so widespread in western Europe, nor felt shoes, were known in ancient Rus. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Foot-wear can be a unique ethnic indicator of the mixed composition of the urban populations of ancient Russia. For example, the peoples of the Volga Region of the 9-10th centries, that belonged to Finno-Ugric group, bore unique cut porshni. Specifically, such porshni are found in Beloozera. Bashkami with the characteristic elongated heel piece are genetically connected with the Pan-European form of foot-wear, passing out of the deepest past. On our territory they are found in the early layers of old Ladoga and in a number of cities of northwestern Russia. (Kolchin)

The finds of foot-wear in the cultural layer of Old-Russian cities can also serve as chronological identifiers. The forms of foot-wear evolved, changing the technology of their production and use of ornamentation. All this gives the possibility of dating, especially for finds in cultural layers with unclear chronology. (Kolchin)

Stockings, chulki, onuchi, obmotok, portyanki, portyanitsa, podvertki, etc.:

-

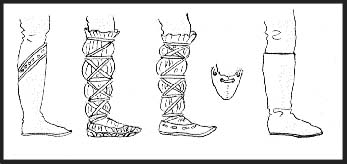

Onuchi are long (up to 2 meters) narrow strips of fabric wrapped around the

lower leg. (Kireyeva) These were often wrapped with the straps from the

sandals, bast shoes, or porshni-postoli. (Stamerov)

As "socks", women would usually only wear the onuchi wrapped around their

feet. They might also wear knee-length woolen stockings. (Stamerov)

In the archaelogical monuments are known diverse parts of clothing, which were preserved almost completely. Frequently are found also knitted [vyazanye] woolen socks [noski], stockings [chulki] and shoes [tufli]. [vyazanye - term means not only knitting, but also crochet, binding, tying… so perhaps these items were made by naalbinding? Sprang? Other?] (Kolchin)

Some re-enactors (Bykov and Kuzmin) propose that wealthy Rus wore Western-style hosen over their Russian-style undertrousers.

It is possible that on the lower part of the leg already in the 10-13th centuries were worn nagolenniki, nogovitsy [наголенник, ноговица - leggings] (Sreznevskij, II, stb. 462). In any case, the Arabian traveler Ibn Fadlan noted such gaiters in the clothing of the elite Slavs buried in Bulgaria in the tenth century (Ibn Fadlan, p. 81). But evidently, as also later, nogovitsy were accessories of clothing of rich persons. Peasants and poor city dwellers wound around the shin and foot over their pants onuchi, long narrow strips of material like later puttees. Onuchi and kopyttsa [копытца], wool socks (Paterik, p. 26) were worn on the shin also by women. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

All the more widespread were chulki, "knitted" (naalbinding?) and sewn of silk material (!). Warm chulki were lined iwth fur. The length of the chulki varied. In the description of the property of Ivan the Terrible were listed "full" and "half-full" chulki. Chulki were worn with garters. One author considered that the "knitted" chulki were distributed only in the 15th century. Another distinguished "chulki knitted of German make". However, "knitted" chulki were also of local production. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

-

The most archaic form of foot-wear, which existed in ancient Russia, is lapti [bast sandals], plaited from the bast [inner bark] of linden, birch and other species of tree. As the researchers of clothing assert, they were known in the Stone Age. In the early layers of Old-Russian cities they are almost unknown. In Novgorod discovered only one bast sandal, found in the 15th cent. layers. For the existence of lapti in earlier times they give evidence of finds of instruments for the weaving of lapti - weaving tools [kochedyk], besides the presence of woven foot-wear in tombs. (Kolchin)

In antiquity, there were several names for foot-wear of the lapti type: "lych'nitsa", "lychak'" and "lap't'", derived from - "lapotnik'" - known in the written sources and going back, in the opinion of research, to the proto-Slavic [praslavyaskoj] epoch. (Kolchin)

In the 9th-13th cent., the most widespread men’s and women’s shoes were lapti, lychenitsy, lychaki [лапти, лыченицы, лычаки] shoes, woven, as shown by the very name, of wood bark or bast [luba] - bast [lyka]. Bast lapti were primarily peasant shoes. Already the first record of them in the chronicle at the end of the 10th century (under the year 985) contrasts the “laptnikov”, the peasant, with the more wealthy city dweller, who wore boots. “Better to have legs dressed in bast in your home, rather than in soft boots in boyars’ court” [Лучше бы ми нога своя видети в лыченицы в дому твоем, нежели в черлене сапозе в боярстем дворе] wrote Daniil Zatochnik to his father, prince Yaroslav, in the 12th century. Thus, lapti were mainly a peasant shoe. But they are significantly older than the peasantry. Kochedyki [кочедыки], instruments for weaving lapti, are found in the settlements of the early iron age forest region of European Russia from the first millennium C. E. Lapti, as with other woven things, were made not only by peasants but also city dwellers. Bone and metal kochedyki are found in pre-Mongol layers of small cities. Lapti were woven in every family for their own needs, in that connection this was man’s work, just as spinning and weaving was the domestic occupation of women. Not for nothing was widespread the little bast picture in the 18th century showing such a family idyll: “The husband lapti weave, the wife thread spins” [Muzh lapti pletet, zhena nitki pryadet.]. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

The most widespread men's and women's shoe in the 13th-17th cent. was lapti. They were worn by almost all peasants and sometimes city dwellers. There was even a lapti production industry. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

The earliest image of lapti dates to the 15th cent. On a miniature from Sergius Radonezhskiy's Life is presented a scene of ploughing with the peasant in lapti. Townspeople, obviously, did not wear lapti. Probably, lapti were work foot-wear, connected with the field work. Lapti were always, up to 19-20th cent. worn by the poorest people. (Rabinovich, 9-13th?)

Lapti or "sandals" could be worn tied on with special lacing threaded through eyelets on the sides of the sandal. (Kireyeva) And they were worn mostly by rural inhabitants. (Pushkareva89)

Lapti were fastened by means of long strings, obory, passed through the side of the lapti and wound around the feet. Foot-wear from bast were worn over the stockings, the socks, nogavits [nogavits, hose?] and windings [obmotok, leg wraps].

Lapti were usually woven of bast (the inner bark of larch or birch trees). The bark was prepared by soaking a long time, then straightened under a press. It took 3 or 4 saplings to make such a pair of shoes, and a pair might last only a week, even those woven "with podkovyrkoj" (double sole). (Pushkareva97 and 89)

Such shoes could also be woven out of strips of coarse leather. These were more durable than bast, but also more expensive. (Pushkareva97) So in order to combine low price with durability, in the country they often used combined weaving of lapti from bast and leather straps. In cities lapotsy in 12-14th cent. were made also of "cuts" of fabric, little pieces of smooth wool cloth and even of silk ribbon. In that case they were called pleteshki (wicker/weaving). (Pushkareva89 and 97)

During the 9th-13th cent., in the cities, the weaving of shoes was a bit improved: in excavations we find lapti of mixed weave: bast including leather straps on the sole or even lapty fully woven of leather straps. Thus appears to improve the quality of the shoe. Lapti of bast were worn very briefly: in winter, a week to ten days, in summer in the working times, 3 to 4 days (Bakhros, 1959, p. 32). One must think, that in cities, the roadways decreased the period of wear of the lapti still more and to reinforce the sole of the lapti with leather was extremely advisable. Possibly for the rich city dwellers were made even some fancy “lapotki” - woven shoes “lapottsy semi silk”, which the Russian bylini, inclined to hyperbole, furnished even with precious stones (Bakhros, 1959, p. 122). After all, lapti had also a well-known advantage over other dense and heavy shoes: in them, for example, was not retained water. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Woven of linden/lime bast lapti were widespread among the eastern Slavs and their neighbors, western Slavs, Balts, Finno-Ugrics, and in all likelihood, as has already been said, came to these peoples from tribes living in the forest belts of the early iron age. And the method of weaving differed in the western regions (later Belarus and part of the Ukraine), where were widespread lapti of “straight” weave (right angle squares), and eastern (later great Russian), where predominated lapti of angled weaving (slanted squares) (Bakhros, 1959, page 23). Evidently, this difference dates back to the ancient Slavic tribes. Lapti of angled weave were fairly attributed, for example, to the Viatichi (Moscow or Viatich type) (Maslova, 1956, p. 716-719). Novgorod Slovene lapti were also of angled weave, but not of linden/lime bark, but of birchbark. And lapti of the Radimichi, Dregovichi, Drevlianin, and Polianin could be of straight weave. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Soles from woven leather straps are found in the Lyadinskom tomb and in the kurgan of the Vyatichi. On the basis that on the inner side of the sole from the Lyandinskoj tomb were preserved the remains of the bast tapes of the lapti itself, V.P. Levashova proposed that the woven leather soles from the Vyatichey kurgan could also belong to ordinary bast (Kolchin)

Lapti of the above-indicated tombs had different weaving: the soles from the Lyadinskogo tomb were slanting weaving, the sole from the kurgan of Vyatichey - straight line. [diagonal/bias vs. square] (Kolchin)

Various weaving patterns were used (oblique, straight) depending on the traditions of the ethnic region. The form of laptej also varied depending on locality: southern and Polesski lapti were open, while northern - "bakhili" - had the form of a narrow boot. (Pushkareva89)

Judging by materials of recent ethnography, lapti could be in the form of shoes with low sides, similar to the Polesskij lapti of straight interweaving, and in the form of deep closed shoes of the northern type of slanting interweaving, known in the Novgorod lands. (Kolchin)

An interesting article about making birchbark shoes. Wilderness Survival: Birchbark Shoes.

-

Group 1 - soft leather

-

Type 1 - bashmaki, ankle-high shoes

Type 2 - sapogi and polusapozhki, boots and half-boots

Type 3 - porshni, slippers

Group 2 - "rigid" leather

-

Type 1 - tufli, shoes

-

Subtype 1 - one-piece upper

Subtype 2 - pieced upper

In the cultural layer of many medieval cities, leather is preserved well. In just Novgorod hundreds of thousands of examples of foot-wear of different forms have been found. These include: porshni - low foot-wear, similar to lapti; bashmaki - foot-wear with a little collar at the ankle; boots [sapogi] and halfboots [polusapozhki]- foot-wear with a boot top; and shoes [tufli] - foot-wear with low sides, reaching the ankle.

-

Urban women would not wear bast, preferring leather footwear. The leather

came from horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, or, the most valuable, soft goatskin.

Pickled in kvas, leather was tanned with bark of willow, alder, oak (from

the word for oak "dub" came the very term "tanned" - "dublenie"); smoothed

out, "oiled" for elasiticity and was kneaded. In such a way came about most

expensive sort of leather, "Russian leather", but only noble boyarinas could

flaunt it. (Pushkareva89)

This "Russian leather" was colored in bright colors, evidenced in both princely miniatures, and frescoes, depicting noble women. The mother of Yaropolk Izyaslavich from Trirski psalter is shown wearing little red shoes; and such also had the wife of Svyatoslav Yaroslavich (Izbornik 1073), and a wife of a Novgorod boyar in a 15th cent. icon. Archeological finds confirm that the colors of leather women's shoes were various - not only red, but also zelenovatymi (green-?), yellow, brown. (Pushkareva89)

Noble women might wear everyday shoes made of colored leather or thick fabric with pointed toes that could be as high as the ankle. These were decorated with embroidery and even pearls. (Stamerov)

Soft "Russian leather" of different colors was not affordable for simple Rus. They wore plainer shoes of rawhide leather - so-called porshi. But even everyday shoes had some sort of ornament - embroidery, cut-outs, or beads. (Rabinovich, 9-13th? Kolchin?)

In the large commercial cities like Novgorod and Pskov, inexpensive professionally made shoes replaced homemade shoes in the 13th and 14th centuries. Large cobbler's workshops flooded the marked with mass-produced footwear in a limited number of styles. (Pushkareva97)

-

This is the most ancient form of leather foot-wear in Russia. Bashmaki are discovered in Staraya Ladoga in the layers of the 8-10th centuries. This is soft foot-wear of tanned cow's or goat skin with lapels/sides higher than the ankle. Using the method of cut - from one-piece piece or from two pieces of leather - bashmaki can be divided into two subtypes. One-piece were cut from large pieces of leather, then the parts of the cut were sewed with stitches/thread [?tachnym] and inverted seams. The one-piece bashmaki are found in Novgorod and old Ladoga, and in other cities of the 10-13 centuries. A bashmak from a single piece of leather was found on the Raykovetskyy fortification. (Kolchin)

Soft shoes, reminiscent of modern children's pinetki, were a widespread type of women's leather shoes. The majority of such shoes had a small strap let in at the ankle, and tied up in front on the instep. The length of the footprint in actual examples of women's shoes does not exceed 20-22 centimeters; indicating that the feet of city dwellers of that time were quite small. (Pushkareva89)

In old Ladoga among the early bashmaki are known those made of two pieces of leather for the top and the sole. Bashmaki of two pieces of leather are widespread in the strata of Old-Russian cities of the 10-13 cent. Two versions of their cut are known: with the seam on the side and with the seam in back. (Kolchin)

Materials from the excavations of old Ladoga, Pskov, Novgorod, Beloozera, Minsk, old Ryazan. Ancient Grodno, Moscow, Polotsk, Old Russo, and other cities give evidence of a united tradition in the production of Old-Russian bashmaki beginning in the 8th cent. This unity is expressed in the existence of bashmaki of identical cut in all Old-Russian cities. Special bashmaki with an elongated heel predominated only in Beloozere, because of the specialization of leather working in this city. (Kolchin)

One special feature is characteristic for the bashmaki of the 8-9th centuries: their soles do not have sufficiently clear outline for the right and left foot, although the cut of the top is asymmetric and calculated for the right and the left of the foot. The soles of ancient Russian shoes are sewed to the top with a turned seam, the details of the top sewed with tachnym seam. (Kolchin)

The Old-Russian bashmaki of the 10-14th centuries were fastened with the aid of a strap, passed through rows of holes in the region of the ankle. With this method of fastening the shoe was suitable for a foot with any instep. (Kolchin)

Bashmaki were decorated with embroidery, in 8-10 cent. mainly by ornamental stripes on the middle of the toe. They made them via piercing of small stitches. (Kolchin)

In the 10-13th cent. bashmaki were decorated with more diverse embroidery. Foliage-geometric ornament predominated. Are found bashmaki with pattern not only in the form of flights/sprouts [pobegov], krinov [fleur-de-lis like motifs], which present plant -flowered [rastitel'no-travchatyj] ornament, but also with the pattern in the form of diamonds, circular and arrow-shaped figures. They were embroidered with woolen, flaxen and silk threads. They were colored into red, green and other colors. The outlines of figures were embroidered by a "back needle" seam [back-stitched?], or as it is still called, "verovochkoy". Besides embroidery, shoes were decorated with the aid of colored threads and narrow straps passed through rows of holes in the leather. (Kolchin)

In the 13-14th cent., as the adornment of shoes they began to employ stamping. Usually these are along parallel incisions between elements of plant-geometric ornament on the toe of the shoe. (Kolchin)

The subjects of the embroideries on the shoes indicate the unity of ornament on the articles of daily life and art. Analogies with the patterns of embroideries can be found on the fabrics, on adornments with enamel, in the carving on wood, and also on frescoes. (Kolchin)

In ancient Russia, besides the general names for foot-wear [obuvi] - "obushcha", "obutel'", "obutiye", known from the 11 cent., there existed a large quantity of names connected with specific types of foot-wear. Bashmak is the most recent of them and moreover is clearly borrowed from Turkish languages. It appeared not earlier than the 15th cent. (Kolchin)

Earlier in Russia, to refer to the soft bashmaki, they probably used the term "cherev'ya", which comes from the pan-Slavic vocabulary. It comes from the name of the material - soft leather from the chreva (stomach) of animal. It is possible to propose that the term "cherev'ya", which is encountered in the Povest of Vremennykh Let under the year 1074 and interpreted by Sreznevskim as the various types of foot-wear, referring to that very type of foot-wear, which will later be called bashmaki. This is all the more probable since the word for "bashmak" in the Ukrainian language is the word "chervik". (Kolchin)

Old-Russian bashmaki are depicted in the miniatures of the Radzilvillovskoy chronicle. (Kolchin)

Bashmaki in the 10-13th cent. were typically urban foot-wear. But, judging by the findings in the kurgans, they were worn also by the rural population. (Kolchin)

During the 13-17th cent. boots, like bashmaki, were made of different sorts of leather. Expensive ones were not only black or red, but also yellow and green. A special variety of colors distinguished Moroccan leather shoes. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Styles of boots and bashmaki changed with fashion and the availability of various types of leather. The more ancient shoes were made of soft, thin leather and so were made with the turned method. The sole was made of several layers of leather. Such boots survived into the 17th cent. But beginning in the 14th cent, there appeared also thick, hard soles. The toe of the boot or bashmaki, depending on the fashion, was rounded or a little turned up (the narrow toe of the sole was sewn with a special slit in front for this). In the majority of cases, the sources do not distinguish between work shoes, every day shoes, and holiday shoes of men and women. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

-

I.S. Vakhros derives the term "porshen’" from the proto-Slavic "r'chkh". The words formed from this root indicated anything soft, loose: porshni made from soft leather, from the loose parts, located on the belly of animal. The Old-Russian designation of porshni - "prabosh'n'" is encountered only in the concepts of the 14-15th centuries, and for the living language of our time it is not characteristic. (Kolchin?)

In the miniatures of the Radzivillovskoy chronicle [15th cent. copy of a 13th cent. original], porshni are depicted repeatedly. On the basis of the data of excavations and graphic material the researchers of the foot-wear of are inclined to consider porshni the foot-wear of the poorest townspeople and peasants. (Kolchin)

Simple leather shoes were porshni (poraboshni, postoly, morshni) [поршни, порабошни, постолы, моршни] They were made usually of one rectangular piece of rawhide leather. Possibly, originally on this shoe was sewn even not of leather but the unprocessed skin of wild or small domestic animals. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In the 9th-13th cent., porshni were widespread among peasants, however, evidently, somewhat less than lapti. Among city dwellers they were considered poor shoes. Worn, full-of-holes, and patched porshni and their remains are frequent finds in the cultural layers of Russian cities. In Novgorod, old Ladoga and Moscow along with simple porshni, are left pieces with sewn paired corners and a cord passed through the upper edge, and find also openwork porshni, decorated on the nose with slits. There were also porshni sewn of two pieces of leather. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Porshni and lapty were fastened to the shin with long leather povorozami or hemp oborami, crisscrossed a few times on the shin over the onuchi. Slanted squares are often drawn in antiquity on the shins of people shod in lapty or in porshni. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In the 13th-17th cent, besides lapti another type of shoe was popular among ordinary citizens - porshni of approximately the same design as in the 9-13th cent. Such shoes and their parts are found in urban excavations, but less often than other leather shoes. Different types were considered morshni or uledi, made of oxen rawhide and combining, apparently, a leather bottom with a felt upper. In Moscow, in a 16th cent layer was found part of a leather shoe, which, in addition to a felt insole, was lined with felt so that the foot was covered above. It may be that this was a piece of uledi. Is also known a shoe of the porshna type called stupni. One foreign merchant, living in Pskov in the 17th cent. translated this term to the German word, Schuhe. (Rabinovich, 13-17th).

Porshni were the simplest and most widespread foot-wear in ancient Russia. It is possible to divide them into two subtypes: one-piece (subtype 1) and detailed-pattern or composite (subtype 2). They were made not only from the soft tanned leather, but also from raw hide. (Kolchin)

The leather for "porshnej" was not tanned, but only kneaded and saturated with oil/grease. These shoes were durable but not waterproof, and quickly saturated in rain. They were sewn with linen threads, which for durability were sewn in. (Pushkareva97)

Soft women's porshni with a small number of "shoe makers" could be made of the more thin and delicate parts of leather of animal, mainly from the "chreva" - belly; they even were named "cherev'ya" (cherevichki). Around the edges of porshni, small leather straps were passed through, which tightened the shoes around the leg, forming small pleats/wrinkles, and also ornamenting the shoes. Everyday porshni and cherv'ya were embellished only with unusual shvami ("pleteshok" [weaving?]). (Pushkareva89)

Holes would be repaired with decorative leather patches. (Pushkareva97) One form had no seams - the leather was simply cut in an oval and gathered around the ankle with a drawstring threaded through slits in the leather. (Pushkareva97)

One-piece porshni were made from a piece of leather of different forms. For the first version of cut was used a rectangular piece of leather. The porshni of the 11-13th cent. were made via the simplest gathering of the piece leather in the region of toe and heel with a bast or leather lace, passed through the single cuts on the sides. The laces tightened the porshni and were tied around the leg over the pants, the stockings or the leg wraps. Such porshni existed in the life of peasants up to the 20th cent. (Kolchin)

Using the method of formation the porshni of rectangular cut can be divided into several types. Thus, besides the simplest gathering, some porshni were made in such a way that, with the formation of toe, was formed beautiful weaving [pleteshok – better translated as pleating here?]. (Kolchin)

Another form had the leather turned up at an angle at the front and sewn to make a toe, then the sides and back were turned up and threaded with straps that were then wrapped around the shins over the onuchi. (Stamerov)

In the 14 cent. in the layers of Old-Russian cities appear porshni whose toe and heel are no longer gathered with a strap, but are sewn by threads, this is related, obviously, with the use of harder leathers. (Kolchin)

Unique porshni existed from the 10th cent. in Beloozere. They were also made from a rectangular piece of leather, but had unique cuts in the region of the toe. Such porshni were not gathered, but were sewn. (Kolchin)

Second version of porshni made from a whole piece of leather are porshni from a hexagonal [more or less] piece of leather. Along the edge of toe and heel they are supplied with holes for the tightening with the lace, and along instep and toe were arranged diagonal cuts for the lacing. Along the sides there were also cuts. The lace passed through them to attach the porshni to the foot. This strap support is later called "oborami" . Such porshni in the scientific literature are called "openwork" [azhurnymi]. They are known in the layers of Old-Russian cities since the 11th cent. (Kolchin)

Openwork porshni were far more stylish. They were often made with a cloth lining. The pattern of openwork presented itself most often of all as parallel slits, little stripes. (Pushkareva89)

Besides openwork from 10th cent. existed embroidery of shoes with wool and silk threads, and also stamping/embossing them. Openwork and embroidered porshni appeared in cities (Novgorod, Grodno, Starij Ryazan, Pskov) no earlier than 11th cent. (Pushkareva89)

Kolchin's subtype 2 is porshni made from several parts. It is known in two versions of the cut: of two and of three parts. The porshni of the first version are known in Novgorod from the 11th cent. Major portion of its preparation includes sole, counter/back and sides. It takes the form of an irregular rectangle with blunt/cut-off angles in the toe part. The smaller fragment of the pattern took the form of triangle. The main blank/piece was bent around the foot, and the triangular piece was sewn in at the instep. The cuts for the passing of lace were located along the sides of the porshni. (Kolchin)

The porshni of the second version consisted of major portion of the pattern, which included sole and counter, the separately undercut [?podkroennogo] toe of triangular form and strips of leather sewn on the side with transverse cuts, through which the lace was passed. All parts were sewn with threads. In old Ladoga was found an entire porshni of this version. It is dated to the 16th cent. Thus, porshni of three parts can be considered as the result of the development of the porshni of the pre-Mongol era. (Kolchin)

-

In ancient Rus from the 9th-13th cent. are often met more complex leather shoes, sewn of several pieces, from sewn on soft podoshvoj ( this very name from the word, “podshivat’” [to sew on]) and at least, covering the whole foot, some higher than the ankle. The front edge opened at the instep of the foot. Evidently, this could take, as in sources from the 10th century, the name cherevik, chereviki. [черевик, черевики] The origin of this name is connected, evidently, with chereviem [черевием] , leather from the chreva, the belly of the animal (Bakhros, 1959, page 192). Chereviki are met in excavations in cities, and very rarely in rural kurgans. This was, consequently, a shoe of city dwellers, which was worn also by wealthy peasants of nearby villages. Chereviki were found, for example, in a kurgan of the 13th century d. Matveevskaya to the south of Moscow (Latysheva, 1959, page 52–54). (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

For the 9th-13th cent., the rather complex pattern and the existence of soles allows us to suppose that chereviki were made already by specialist-bootmakers. Porshni sewn of two pieces of leather were called chereviki among the western Slavs (Bakhros, 1959, page 40). (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In cities, more widespread than lapti and porshni during the 13-17th cent. were choboty, chereviski and sapogi. Choboty and chereviki differed from boots mainly in that, like later shoes, they were short, without a boot top in the actual idea of the word, and in front could have a slit, or else were gathered around the leg on a cord. In excavations in Novgorod, Moscow, Peryaslavl, Ryazankij and other cities, parts of choboti and chereviki are found often, usually in layers from the 13-15th cent. Among them are even some richly decorated with bossing or openwork ornament. In later cases, colored threads were passed through little holes making many-colored patterns. The majority were made of black leather, but there were also ordinary choboty of various colors and material - Moroccan leather, satin, and velvet - the fabrics ones with embroidery. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

-

As we could see above, the elements of rigid form - the strengthening leather padding - were used in some types of Old-Russian foot-wear even in pre-Mongol time. Finally the tradition of the production of foot-wear of rigid forms was formed more recently, in the 14-15th centuries. The earliest type of the foot-wear of rigid form could be considered the shoes [tufli], the characteristic feature of which was the presence of rigid sole and low sides. (Kolchin)

According to their cut they are divided into two subtypes: shoes from the one-piece upper and sole (subtype 1) and shoes from the pieced-cut upper and sole (subtype 2). (Kolchin)

For preparing shoes of the first subtype, two versions of the cut used: with the seam at the side and with the seam in back. Shoes were fastened together by laces on instep or on the inside of the ankle. Sometimes they were decorated with thread on the instep, analogous to similar shoes existing in the medieval cities of Western Europe, especially Polish. (Kolchin)

The shoes of the second subtype (pieced-cut) are known from the finds in Minsk, in the layers of the end of the 13th cent. The development of their form is encountered in old Ladoga, in the layers of the 16-17th centuries. They have a deep head/cap with a tongue on the instep, a composite counter/back with lining/packing [prokladkami], three-layered sole with the wide low-set heel, which was fastened with wooden pins and sewn with waxed thread. The details of the upper were sewn with a tachnym seam, and the upper attached to the sole like a sandal [?]. Shoes were held on the foot with the aid of a strap, which was cut together with the internal half of the counter/back and was passed through the cuts on the tongue. (Kolchin)

Wide distribution of shoes [tufel'] in Western Europe and the concentration of their finds in the western regions of Russia make it possible to connect their appearance with the resurrection of the western contacts by the Russian state. However, the prerequisites for the appearance of foot-wear of rigid forms already existed in the leather work of pre-Mongol Russia. The described foot-wear makes it possible to trace the succession of the types of cut and ornamentation from the 10th century up to the period of Muscovite Rus. (Kolchin)

Boots

-

Old-Russian name "sapog'" is of Turkish or Pre-Bulgarian origin. In the beginning of the 2nd millenium this term, in the opinion of I.S. Vakhrosa, displaced the Slavic name of the foot-wear with the high boot top - "skr'nya" (designating the skin of an animal). (Rabinovoch, 9-13th?)

- An analogous boot was found also in later layers of Novgorod, its boot top had holes made for passing a strap through.

- Soles in such boots had rounded outlines for the toe and heel. The upper of the boot was sewn with a tachnym seam, the soles sewn on with inverted seam. They were worn by youth and children. Versions of similar boots are known from the findings in Pskov.(Kolchin)

- In the layers of the 11-12th cent. is discovered a boot, whose upper consisted of three parts. (Kolchin)

- Also interesting are the boots found in Pskov in a 12 cent. building. The upper of their consisted of two parts: single-seam boot top and cap/head. Both versions of the cut of Pskov boots had soles with the rounded outlines of toe and heel. The boot’s upper was sewn with tachnym seam, soles were sewn on with an inverted seam. On the boot tops were placed cuts for passing through a strap. The described boots belonged to adolescents. Obviously, the Pskov boots were later in comparison with the Novgorod. In them can be traced the development of the gradual detailing of cut, the defining of the head into an independent detail. The tendency toward detailed patterns is a chronological feature characteristic of all types of foot-wear. (Kolchin)

- Boot tops analogous to those of Pskov, are found also in Polotsk. They have a flared form and cut for passing through a strap. Judging by the boot tops found in Novgorod, such boots were attached to the foot not only around the ankle, but also under the knee. (Kolchin)

For the boots of the second subtype (pieced-cut) is there is further detail in cut, in particular the isolation of the counter/back. Similar boots are found in Novgorod and Pskov. They have not only such independent details as heads/caps and counters/backs, but also leather linings under them for strengthening the lower part of the boot, which indicates a tendency leading toward the origin of the foot-wear of rigid forms and, later, in the 14-15th centuries, will lead to appearance of the heel. (Kolchin)

- In the 10-13th cent. were many transitional types of boot; therefore in the layers of Old-Russian cities are found not only the counters/back of various pattern, but also seamless/solid boot tops, designed for soles with both rounded and elongated outlines in the region of the heels. They seemingly repeated the cut of the bashmaki of the time. Rarely are encountered boots with the elongated turned-up toe. Such boots will become popular in the 15th cent. (Kolchin)

- All boots of 14-16 centuries maintained the traditions of the cut of the pre-Mongol boots: counters/backs with triangular cut and soles with elongated tongues, which carry the design and decorative significance. Even the composition of the heel was the result of the refinement/development of the multilayer padding in the sole of boots, which existed in the 12th cent. (Kolchin)

- Thus, in the development of boots a known sequence is observed. Judging by the Novgorod findings of the 10-11th centuries, their quantity is still small. These boots are seamless/solid. Then appear boots of detailed-cut/pattern. In the 12th cent. they coexist. Further appear the boots of rigid form, which in the 14th cent. displaced both the soft boots and soft shoes. (Kolchin)

In the 10th-13th cent. boots were short in the toes and high in the back. These had high soft tops that were cut straight across Some boots of the nobility had turned-up toes. These generally had tops cut at an angle. The boots were sewn from hide dyed black, brown, and dark yellow. Those of the nobility could be red, violet, dark blue, or green with tooling and embroidery in stripes, circles and dots. (Stamerov)

"Half boots" (polusapozhki) of city dwellers were short and not stiff - the back of them lacked hard padding from birchbark or oak, obligatory in boots. Such shoes, "half-boots" were ornamented with embroidery. Among embroidery of shoes of Pskov of 12-13th cent. predominate small red circles (solar symbols), "proshvy" of dark threads (portrayal of road) and green flourishes (symbol of life). (Pushkareva89)

From the 12th cent, the favorite footwear of well-to-do inhabitants of ancient Russian cities were boots - blunt-toed or sharp-toed (depending on the traditions of the given area), with the toe a little raised up. Pskovskie boots always had a narrow little composition leather heel (from 14th cent.), while, for example, Ryazanskie were distinguished by a triangular leather inset on the toe. Bright little leather boots with edging material and embroidery of colored threads, river pearls appeared as an addition to the stylish and holiday garb of wealthy women, as a distinctive indicator of the income of family, as a necessary attribute of the garment of a personage, shrouded with authority. (Pushkareva89)

Aristocratic women might place orders for boots or half-boots for feasts months in advance. The leather for these boots was cured in kvas, then tanned with willow, alder or oak roots, scraped, stretched, greased, kneaded and dyed various colors. The tops of dress boots were decorated with embroidery, leather braid, cut-outs or metal studs. The toes were made especially elaborate to attract attention from under long skirts. Heels were 2-3 inches high (Muscovite period), made of horizontal layers of leather or a solid core wrapped in leather. Bridal half-boots were decorated with pearls. (Pushkareva97)

Among embroidery of shoes of Pskov of 12-13th cent. predominate small red circles (solar symbols), "proshvy" of dark threads (portrayal of road) and green flourishes (symbol of life). (Pushkareva89)

The rich wore boots. An indispensable part of princely clothing were the colored boots, frequently embroidered with pearls and plaques. Thus, on the 12 cent. fresco in the church of Spatsa-Nereditsy in Novgorod, Prince Yaroslav Vladimirovich is depicted in yellow boots, decorated with pearls. In the "Izbornik of Svyatoslav" 1073 on the group portrait of the family of Svyatoslav it is possible to see the earliest image of boots with the characteristic turned-up toes: Prince Svyatoslav - in the dark-blue boots, and his son Yaroslav - in the red. (Kolchin)

- Soles in such boots had rounded outlines for the toe and heel. The upper of the boot was sewn with a tachnym seam, the soles sewn on with inverted seam. They were worn by youth and children. Versions of similar boots are known from the findings in Pskov.(Kolchin)

In the 9th-13th cent., the most widespread shoe for city dwellers were sapogi, [boots] which peasants almost never wore. Not for nothing did the chronicle parable of the 10th century cited above contrast peasant-lapty-wearers with city dwellers shod in boots. The remains of boots are met in excavations in cities extremely often - much more often than the remains of chereviki, porshni, and much more than lapty. In artisan areas, where the leather–boot workshops were, boots are met often - in the tens and hundreds, and scraps, in the thousands. The very name of this type of shoe, sapog, is found, as has already been said, in ancient Russian sources already in the 10th century, researchers, however, do not consider this a native Russian term, but traced ancient Turkic or pro-Bulgar (Bakhros, 1959, p. 207). Ancient Russian boots had soft soles sewn from several layers of thin leather, somewhat pointed or blunt noses, and rather short boot tops, lower than the knee. The upper edge of the boot top was cut at an angle, so that the front was higher than the back, and the seams were set along both sides of the leg (Rikman, 1952, p. 39; Isyumova, 1959, p. 212-214; Rabinovich, 1969, p. 286-288). Smart boots were decorated with trim material along the edge of the boot top, and sewn with colored threads and even pearls. Heels and hard soles among the finds of boots in excavation from the 10th to 13th centuries are usually not traced. They sewed boots on a wooden shoe last without a difference between the left and right foot; either these were broken in on the foot, or were worn alternately on the right or left. Judging by archaeological finds, in boots were shod city dwellers rich and poor, men, women and children. The boots of rich city dwellers were distinguished with better manufactured leather, bright colors (yellow, red et cetera.), and expensive embroidery. Boots, like both cherviki and lapty, worn in all likelihood over onuchi, portyaki or chulok [puttees, leg wraps, stockings?]. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In cities, more widespread than lapti and porshni during the 13-17th cent. were choboty, chereviski and sapogi. Boots (the most widespread shoe of city dwellers) had, as in the previous period, a relatively short boot top. "The boots they wear forthe most part are red and moreover very short, such htat they do not reach to the knee, and the sole is nailed on with iron tacks" wrote Gerbershtejn in the 16th cent. Boots, like bashmaki, were made of different sorts of leather. Expensive ones were not only black or red, but also yellow and green. A special variety of colors distinguished Moroccan leather shoes. Embossing was widely used as decoration, by which a more complexs pattern was imprinted on the boot top, and on the front of the boot was embossed an imitation of the natural creases of the leather, but more regular and fine. Besides that, sometimes the edge of the boot top was decroated with colored material, and the whole boot covered with valuable embroidery. In 1252, Prince Daniil Galitskij wore "green sapogi, gold embroidered". (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Styles of boots and bashmaki changed with fashion and the availability of various types of leather. The more ancient shoes were made of soft, thin leather and so were made with the turned method. The sole was made of several layers of leather. Such boots survived into the 17th cent. But beginning in the 14th cent, there appeared also thick, hard soles. In 110 fragments of boots found in the 14-17th cent. layers in Pereyaslavl Rysazanskij, 103 were of hard construction, and only 7 were soft. With this change, gradually changed to sewing symmetrical soles. In the cases of soft shoes mentioned above, even the soft shoes were made assymetrical: on the left or right foot, with only one made symmetrically. Soles were sewn to the front and, for strength, nailed on with nails and on the heel place a "horseshoe", and the back packed with birchbark. The toe of the boot or bashmaki, depending on the fashion, was rounded or a little turned up (the narrow toe of the sole was sewn with a special slit in front for this). In the majority of cases, the sources do not distinguish between work shoes, every day shoes, and holiday shoes of men and women. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

For the 13-17th cent. besides choboty, chereviki and sapogi, one researcher identified also "half-boots" - with a shorter boot top and a soft back without birchbark packing. However medieval written sources do not have this term, and we are forced to consider the half boot as a type of boot. (Rabinovich, 13-17th)

Boots and halfboots were the favorite type of foot-wear in Russia. They differed from each other only in the height of the boot tops, and their development occurred in the same direction; therefore they can be examined in a single typological series. The boots of pre-Mongol Russia can be divided into two subtypes: boots cut from a large piece of leather with a seamless/solid boot top and those cut from several small parts. (Kolchin)

The first subtype has many versions of the cut. One of them is presented in the boots from Novgorod. The upper was solid/seamless [tsel'notyanutym], about which the cut gives evidence. The tops of boots [golenishcha] are made of two halves, the forward section forming the head/cap [golovku] and then the boot top, and the rear corresponds to counter/back [zadniku] and also forms the boot top. This example is the earliest model of boot. It is dated to the 11th cent. (Kolchin)

Comments and suggestions to lkies@jumpgate.net.

Back to Early Rus Clothing.

Back to Russian Material