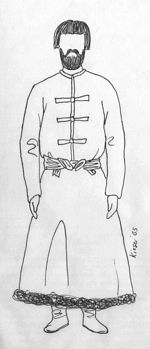

One version of the svita.

Another version of the svita (shuba?).

-

"Opashni" and other such narrow-sleeved outer garments (odnoryadka, shuba, etc.) could be worn over the shoulders, cloak-like.

(Pushkareva89) and (Bykov/Kuzmin) and (Rabinovich)

See Layers 2 and 3.

-

For the 9th-13th cent., better studied are upper cloak-like garments of many forms.

In the period of the 13-17th cent. sleeveless cloaks gradually receded to the background in the set of Russian clothing. Among sleeveless cloaks recorded in the 14th century are: the votola, kots, myatl' and the epancha.

Votola:

-

For the 9th-13th cent. the most widespread of its forms, the votola, as shown by the very name, was made originally of thick linen or hemp fabric. This was a sleeveless garment, thrown over the shoulders over clothing of the svita type. It was fastened at the neck and hung approximately to the knee to to the calf. Possibly, the votola even had a hood (Poppe, 1965; SRYa, bysh. 3, p. 73). The votoly were worn in ancient Rus by all, from the “stinker” to the prince. But the princely formal votola was sewn of expensive material. The absence in peasant graves of fibuli, cloak fasteners, compel us to think that the votola of the “stinker,” in all likelihood, was not fastened on a buckle or button, but fastened by some sort of cord. But the precious votola of the elite, sometimes decorated with precious stones, could have also beautiful clasps. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

In the 13-17th cent., for men and women of the common people, upper dress was the same - for example the votoly, sermyaki [?], and svitki [?]. But the votola, by the 14th century seems to considered not decent to wear even for peasants and commoners. Perhaps this is why Metropolitan Kipriana forbade the wear of the votola to confession and communion. (Rabinovich, 13-17 c.)

Myatl':

-

For the 9th-13th cent., the votola was evidently the more widespread form of cloak, used by the poor. Another form was the myatl’ [мятль], recorded in sources of the 12th and 13th centuries. This was not exclusively an eastern Slavic form of clothing: the myatl’ was worn, for example, by Poles. Myatl’ is recorded mainly for princely servants[soldierly service?], but evidently, was not an especially military garment. The rather high fine (3 grivna) was applied if the myatl’ was torn in a fight, which allows us to think that this was not an especially crude, cheap cloak. The cut of this garment is not clear, and the color recorded only one time, black. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

-

Other forms of cloak, the kisa [киса], and in particular, kots’ [коць], were used primarily in the princely-boyar environment (Sreznevskij, I, stb. 1305; Rorre, 1975, p. 16-17). It’s cut is also not known. A.V. Artsikhovskij considers that the kots’ was widespread in Western Europe under the name slavonika, “Slavic cloak” (Artsikhovskij, 1948, page 252). (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Korzno:

-

A long cloak, almost to the heel, fastened at the right shoulder, the korzno (k”rzno, kor”zno) [корзно, кързно, корьзно] was worn, it seems, only by the prince. In any case, all recorded korzno in the written sources are connected with the prince. Even the cloak “korolya” only of Attila in the chronicle was called a korzno (Sreznevakij, I, stb. 1404). The korzno, as a very luxurious garment, is contrasted in church literature with the poor hairshirt (Paterik, page 52). There are numerous depictions of the korzna in icons, frescoes, and miniatures. This always is a precious cloak of bright Byzantine material, sometimes with fur edging. They were worn over clothing of the svita type, which was usually visible between the opening from the right side flap. The person dressed in a korzna had his own right arm free, while the left was covered with the cloak flap. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

The nobility might wear a small Byzantine/Roman-style cloak called a korzna. It resembled the chlamys and was rectangular or semicircular in cut. It could worn fastened by a fibula, brooch or buckle on the right shoulder or in the middle of the chest (a "cloak-mantiyu") and hung down to the ground in wide pleats. The prince's wife wore such a cloak made of red wool (while the prince's was made of the same printed Byzantine fabric as his tunic-talaris) (Kireyeva) and (Stamerov)

Privoloka:

-

Shorter, wider cloak that replaced the long korzno among the nobility in the 13-17th cent. It was sewn of valuable gold material. The tsarist privoloka of Dmitri Donskoj is recorded in the story of the Mamaev battle [fought in 1380]. Privoloka of damask and velvet "with ermine" are recorded in 16th cent. princely wills. It is possible that the privoloki were also military equipment. With richly decorated edging and even voshvy, privoloki were also women's garments. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Epancha/mentenya

-

The epancha, which is also the name of a type of later period kaftan (yaponchitsa, ermuluk) could also be a sleeveless cloak of the burka type [the burka is a felt cloak from the Caucasus]. The warm epancha lined with fur was called also a mentenya. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

Other cloaks - ludu, konunga, oplech'ya

-

For the 9th-13th cent., from other types of cloak in the chronicle are known ludu [луду], the gold fabric cloak of konunga [конунга] Yakuna, or Gakona (PVL, I, page 100). Possibly rich cloaks were also recorded in the chronicle in the year 1216 as embroidered with gold oplech’ya [оплечья], but it seems to us more correct explanation that this name is for a “laid down collar” (Sreznevskij, Idi, 787624), possibly fastened to some clothing or worn separately, like the later barma. (Rabinovich, 9-13th)

See illustration of Ceremonial Clothing on main men's clothing page.

Comments and suggestions to lkies@jumpgate.net.

Back to Men's Clothing or Early Rus Clothing.

Back to Russian Material